Chick, Chick, Hooray! Politics Be Damned, New Yorkers Want Their Chick-fil-A.

By Lauren Elkies Schram May 18, 2016 9:00 am

reprints

Mayor Bill de Blasio recently made some headlines when he said he would not patronize Chick-fil-A because of the anti-same-sex marriage comments made by the company’s head in 2012. He also said he “wouldn’t urge any other New Yorker to patronize” the restaurants.

He was not the only local politician who decided to weigh in on poultry matters. Queens Councilman Danny Dromm called the Atlanta-based chicken chain “anti-LGBT” and urged “believers in equality” to “boycott” the eatery.

Both politicians’ remarks came after Commercial Observer broke the news that Chick-fil-A will be opening an outpost in Queens Center mall this fall—and it would seem a natural comment for the mayor and a council member to make. New York is a city, after all, where registered Democrats outnumber Republicans by more than six to one, and New Yorkers overwhelmingly support gay marriage.

“I think their politics are abysmal and they don’t naturally fit in the culture of Manhattan,” said Michael Green, a marketing consultant who lives in Turtle Bay and is gay. “They’re a commercial organization, and they have every right to try to grow their business,” but he would “absolutely not” eat at the restaurant.

But what is surprising is that this largely seemed to bounce right off a city that’s too busy chowing down on chicken sandwiches at the two new Chick-fil-A outposts in Midtown West to take notice.

Stephen Corsello, a licensed renovation contractor and owner of the company Nailing It (who is gay), has no beef with Chick-fil-A over the chief executive officer’s four-year-old remarks.

“As far as the controversy regarding the CEO’s personal feelings on same-sex marriage, I feel as though they’ve backed off on it enough that continued boycott is unnecessary,” Mr. Corsello said.

Chick-fil-A has proven itself to be one of the rare brands that deflects backlash—no matter how deeply it goes against the grain of its New York customer base. On a recent episode of The Carmichael Show, a character says, “I support gay rights, but I still eat at Chick-fil-A. Like a lot. Like four times a week.” He thinks about this for a second, then adds, “Maybe I don’t support gay rights.”

A 2012 video of three drag queens lasciviously smothering themselves in Chick-fil-A waffle fries and sandwiches while singing an ode to the chain—set to Wilson Phillips’ song “Hold On”—was a YouTube sensation, garnering more than 7 million views and its own Wikipedia page. (“Chow down at Chick-fil-A—even if you’re gay,” was the refrain.)

While Chick-fil-A does not provide sales numbers for its restaurants, the Big Apple eateries have been pretty consistently crowded since their openings. And even when protesters came out on the opening day of the premiere New York City franchisee-operated location at 1000 Avenue of the Americas at West 37th Street last October, the store was “not impacted at all,” said franchise owner Oscar Fittipaldi. (There has been a licensee-run Chick-fil-A outpost in the food court at New York University, open to the public, since 2004.)

Asked for a response to Mr. de Blasio’s comments, Carrie Kurlander, a vice president of public relations for Chick-fil-A, said in a statement provided to Commercial Observer, “New Yorkers have turned out in record numbers since we entered the market last year, and we are thrilled by the strong response. Everyone is welcome, and Chick-fil-A has no political agenda. Our sole focus is on serving great food with fast and remarkable service.”

Retail broker Robin Abrams, an executive vice president and one of the principals of Lansco Corporation, said she was surprised that “some New Yorkers are not boycotting the chain as a show of non-support for [the CEO’s] unpopular point of view.” She added, “However, New Yorkers also have a live-and-let-live attitude and enjoy good food—so they overlook and eat!”

This April, the company opened its second franchisee-run eatery at 1180 Avenue of the Americas at West 46th Street, just nine blocks north of its first one in the city. So far, Jeremy Ezra, an executive vice president at RKF and Chick-fil-A’s New York City broker, said the locations are not cannibalizing each other; they have each cultivated a unique set of customers.

The company’s plan is to likely have around 20 locations in New York City—noticeably fewer than competitors like Chipotle because of Chick-fil-A’s operator model (it’s built around the premise of one store per operator). A spokeswoman confirmed the chain will open three to four more locations in the New York City metropolitan area this year, followed by 10 to 12 more in 2017.

Mr. Ezra, a Chick-fil-A fan since the age of 4, said that landlords like the chicken chain as a tenant because the company negotiates 20-year leases and it comes to the table with no debt.

After opening a few more locations in dense office locations, Mr. Ezra said the expansion will extend to residential neighborhoods, which has worked for the company in other parts of the country. He said there is particular interest in the Columbus Circle area, Midtown East by Bloomingdale’s and the Financial District. “They’re all targets at once,” Mr. Ezra said.

Obviously real estate costs are higher in New York City, but so are the sales and profits.

The location at 36th Street and Avenue of the Americas had no compelling office and residential density but is doing well, said retail broker Chase Welles, a partner at SCG Retail. “This bodes well for the future of Chick-fil-A in Manhattan,” Mr. Welles said, “[because] it did well in an area that’s not a no-brainer.”

To conquer Manhattan real estate Chick-fil-A has adopted a fairly standard approach: It uses a combination of in-house real estate professionals and local real estate brokers for its real estate deals. Chick-fil-A undergoes a request for proposal (RFP), or solicitation process, in situations where local partners are selected, the spokeswoman said, and typically, there are three to five bidders for each location.

CO reported at the end of April that the fast-food chain is coming to Queens Center mall, in Elmhurst, Queens, marking the company’s first move into the outer boroughs. Despite this decision, Chick-fil-A’s expansion plans are focused on Manhattan and Long Island, Mr. Holmes said. New York City, in particular, is a good market for Chick-fil-A, Mr. Ezra said, because of the “density, income and the tourism.” He added, “The New Yorker has come out strong wanting to learn about the brand and come out quite favorably for the level of service and the price point.”

For those who have never tried it, Chick-fil-A can be at once revelatory and standard fast-food fare. CO took a tour with Mr. Ezra of the 1000 Avenue of the Americas locale earlier this month.

An artery-clogging assortment of food came our way: the Chick-fil-A sandwich, the spicy chicken sandwich, Chick-fil-A nuggets (both grilled and fried), a chicken wrap sans chicken, waffle potato fries, its varied sauces and a kale side salad (because, hey, we’re trying to be healthy).

The Chick-fil-A sandwich is the most popular dish nationwide, including at the three-story, 7,000-square-foot 37th Street eatery (5,900 square feet of it above ground), the chain’s largest, Mr. Fittipaldi said. And that’s because of the secret sauce, which is really found in the chicken batter. An employee said while caking the batter onto the chicken breasts, “If this is wrong, then the whole thing is wrong.”

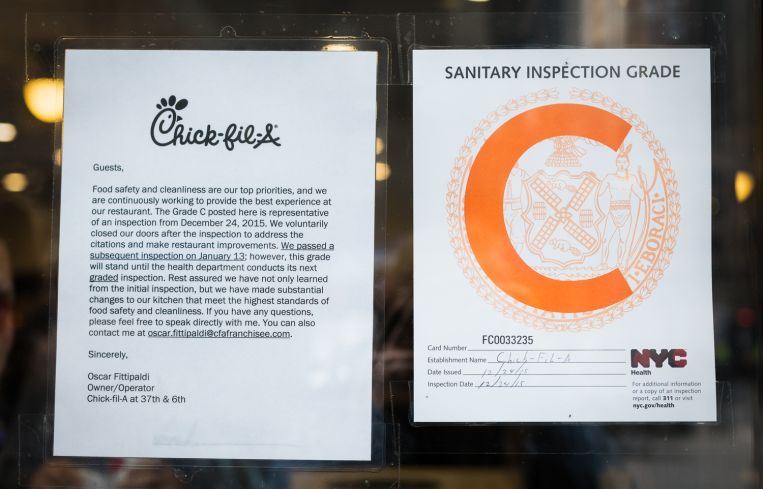

The experience offered highlights and lowlights—the “C” grade from the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene grade in the window was a definite lowlight. (It was appended with a note saying that the eatery voluntarily closed its doors following the Dec. 25, 2015, “C” rating, passed a Jan. 13 inspection, but the grade stands until the next graded inspection.)

The fact that Chick-fil-A is closed on Sundays like all Chick-fil-A locations—“to provide our team members a day off,” said Ryan Holmes, Chick-fil-A’s management consultant of urban strategy—could be viewed as a lowlight or a highlight, depending on where you stand. (Again, it rubs its religious conviction in one’s nose, but it’s also nice to think that an employer insists on giving the employees a day of rest, even if it’s done somewhat paternalistically.)

But the highlights were also in abundance. Mr. Fittipaldi himself was directing the queue, making the service efficient and speedy.

“In New York City, the restaurants aim to provide guests with their meal within six to eight minutes after they place their order,” the company spokeswoman said.

Still, one has to look for the smoking gun—the company’s secret ingredient, which has led to sales exceeding $6 billion at more than 1,900 restaurants nationwide in 2015. What makes die-hard fans in such a liberal city so loyal and so unmoved by the company’s CEO’s opinions?

“We have a supreme product, supreme service and great people,” Mr. Fittipaldi said.

Mr. Ezra commented, “I think it’s service and the quality of the food, and I think it’s the operator model.” Because most of the franchisees only have one location, Mr. Holmes said, they are each “actively involved in the restaurant every day.” Mr. Fittipaldi said he works six days a week, 10 to 12 hours a day.

Indeed, the chain seems to emphasize customer service in a way that one doesn’t see in a McDonald’s or Wendy’s. When CO visited, an employee came over to get soda refills and reappeared again to clean the table after we were done. The ladies’ room was spotless.

“We opened a few downtown locations in Chicago,” Mr. Holmes said. “That was really our first step in operating in urban markets. We learned a lot from those two Chicago locations. We felt we were equipped and ready [for New York City].”

New Yorkers have embraced the fried chicken goodness because “we deliver hot food fast,” Mr. Holmes said. And he noted that some of the fans are people who were missing their Chick-fil-A after growing up on it.

Being a primarily suburban chain where there are parking lots and drive-thrus, Chick-fil-A has had to learn to adapt to the urban landscape of New York City. Manhattan’s delivery and waste systems were largely a mystery when they started, but they’ve since mastered. And Chick-fil-A is replacing drive-thrus with iPad service for ordering while online.

That “reduces the wait time, and people on line can ask questions without being rushed,” Mr. Holmes said. “It will enable us to get people through the lines and quicker. It’s a system that’s been successful, and it’s for urban locations only.”

One retail broker who spoke on condition of anonymity compared the brand with Shake Shack. “They both have low prices, good quality, an iconic experience and excellent marketing,” he said.

Will it become like other chains before it that have grown tired in New York City?

Peter Braus, the managing principal of Lee & Associates NYC, suggested that its glow could fade.

“I can only attribute [the buzz] to [the fact that] New Yorkers like something different,” he said. “I don’t know how long the Chick-fil-A obsession will last. Right now they seem to be appealing to that New Yorker sense of wanting to have something new and different, sort of like when Chipotle came here and the lines were out the door.”