Reimagining a Brookfield Behemoth on the Far West Side

By Liam La Guerre October 21, 2015 9:00 am

reprints

When Brookfield Property Partners was studying how to revitalize the Winter Garden atrium at the World Financial Center (now called Brookfield Place) in 2011, its executives reached out to various design-related firms, including an architecture company that had never completed a project in New York City called REX.

Brookfield just wanted to gather ideas, they said, as plans for a $250 million revitalization of the entire World Financial Center campus were already unveiled that year by Pelli Clarke Pelli Architects, whose founder César Pelli originally designed the center. REX founder and Principal Joshua Prince-Ramus still saw it as an opportunity to create a solution for a space that had trouble attracting patrons to its second-floor retail and dining area. He designed a “floating platform” for the atrium that would serve as an event space on the second floor.

“His concept was amazing. It was clearly the favorite,” Sabrina Kanner, an executive vice president at Brookfield, told Commercial Observer. “We were incredibly impressed not only with the result but also with his process. He thought about it very clearly and intellectually. But as intellectual and articulate as he is, his designs were very beautiful.”

Brookfield didn’t wind up using REX’s plans. But clearly Mr. Prince-Ramus had struck a chord. A few months later, Ms. Kanner called Mr. Prince-Ramus to explain that they wanted him to reimagine the concrete pyramid-shaped 450 West 33rd Street between Ninth and 10th Avenues—a building that even Brookfield didn’t feel any tenderness toward.

“I used to say it was the ugliest building in Manhattan, and then we bought it,” Ms. Kanner said. “We thought of Joshua, because we really needed out-of-the-box thinking for it—someone who didn’t color in the lines.”

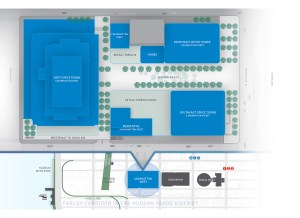

It wouldn’t have been cost-effective to demolish the sprawling 1.8-million-square-foot, block-long concrete building since it sits above Hudson Yards train tracks, so instead Brookfield planned to transform it and integrate the property into its $4.5 billion Manhattan West development, a 7-million-square-foot multi-use mega-complex designed by architecture giant Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, a.k.a. SOM. The full project will include two new glassy skyscrapers: a 67-story Class A office building called 1 Manhattan West and a 62-floor luxury residential condominium tower.

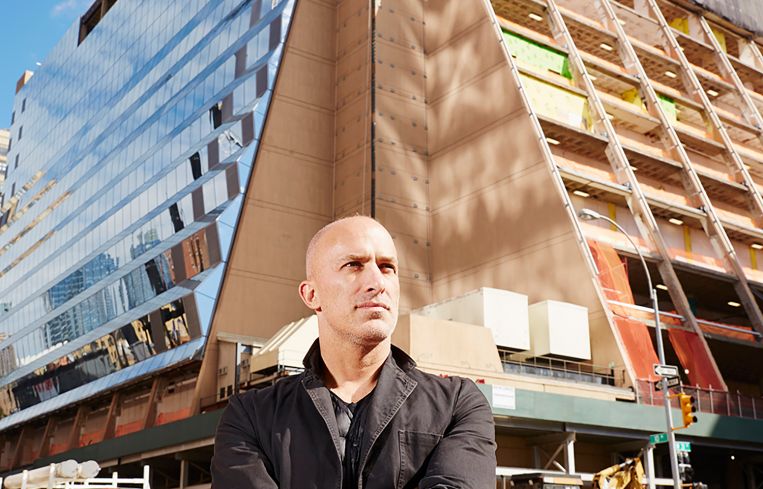

Mr. Prince-Ramus designed the $200 million renovation of the 16-story 450 West 33rd Street (now known as 5 Manhattan West), which many agree finally makes the building shine—literally and figuratively—converting its shell from concrete to glass.

While many well-known tenants have occupied space in the building over the course of its nearly half-century history, including the New York Daily News, Sky Rink (now a part of Chelsea Piers) and the Associated Press (which is vacating for a Brookfield-owned property Downtown, as CO previously reported) for the latter part of its existence, the 1969 building has been ridiculed after misguided updates transformed it from an example of 1960s Brutalist architecture to essentially a mishmash of ideas.

Decades after being built, 450 West 33rd Street—originally designed by Davis, Brody & Associates (now Davis Brody Bond)—went in for a half-baked renovation; it was repainted beige from its original exposed concrete color, and metallic siding was added to cover some walls. The lobby was transformed into a postmodernist style, which didn’t match the building’s exterior.

“It just made it horrible,” Mr. Prince-Ramus said. “I think anyone would admit, regardless of its roots, that it was an eyesore.” (A representative of Davis Brody Bond did not return requests for comment.)

Besides the aesthetic issues, Mr. Prince-Ramus had to solve the building’s energy problems, created by the heavy slabs of concrete panels that make up its exterior. While all-glass buildings aren’t the most energy efficient, Mr. Prince-Ramus’ design compensates for that with a pleated design. The over-slung panes of glass are slightly darkened so it self-shades from direct sunlight with the sloped sides, reducing energy consumption while still allowing natural light into the building.

“I think what he did with that building is nothing short of remarkable,” said Gary Haney, a design partner at SOM, who oversaw the Manhattan West master plan. “It was one of the most reviled and ugly buildings in Manhattan. That skin that sort of folds and cascades is really genius.”

Construction is occurring with tenants still occupying the property; as concrete panels come down, temporary walls are put up. Completion is expected next year.

“There is some inconvenience to the occupants,” Mr. Prince-Ramus said. “They have to pull their furniture in from the exterior. And no matter how we make these temporary walls, it’s difficult to pull off the concrete panels without making a sound.”

But that hasn’t deterred new tenants from signing leases at the property. Along with the promise of its new glassy exterior, the large floor plates of the building (which have a maximum of 140,000 square feet on some floors) and its old industrial ceiling heights that are typically about 16 feet high have been attractive to technology, advertising, media and information technology, or TAMI, tenants.

“We thought of Joshua, because we really needed out-of-the-box thinking for it—someone who didn’t color in the lines.”—Sabrina Kanner

Last year, J.P. Morgan Chase signed a lease for 123,000 square feet on the ninth floor of the building for its digital operations. Advertising firm R/GA also took a lease last year for 173,000 square feet and moved into the space, which comprises the entire 12th floor and part of the 11th floor. And in March, London-based financial data company Markit signed a lease for the entire 140,000-square-foot fifth floor. Asking rents in the building are around $80 per square foot for office space.

“What attracted Markit to the building and what has been vocalized to the real estate community was just a transformation of the building from a building that was just invisible to one that really shines,” said Daniel Horowitz of Savills Studley, who represented Markit in the transaction with colleague Jeffrey Peck. “The interior of the floor plate is going to be flooded with light and that is very important for buildings that have floor plate sizes like 5 Manhattan West.”

A native of Seattle, Mr. Prince-Ramus, 46, is a divorced dad who lives in Tribeca with his 10-year-old daughter. He studied philosophy at Yale University and holds a master’s degree in architecture from Harvard University. Perhaps it’s because of his philosophy background that when it comes to architecture he works to solve problems first and think about the aesthetic later.

He is probably best known for his designs of the Dee and Charles Wyly Theatre in Dallas and the nearly $170 million Seattle Public Library Central Library. The former is an 80,000-square-foot building that features a glass-walled, 575-seat multi-form theater built with flexibility in mind. The theater can transform into a variety of configurations, including proscenium, studio, arena, thrust and a flat surface. The latter is an abstract, blocky, 11-story, 412,000-square-foot building with a full glassy exterior, interwoven with a special metal in a crisscrossing design that makes it opaque to sunlight, but transparent from the inside.

If it looks like various sizes of blocks were piled together in the library’s design, that’s because they were. Mr. Prince-Ramus crafted the levels of the library with sections that cater to different media types, transforming the former library from a generic building dedicated to books to one more adjustable to modern media types. In the largest area, Mr. Prince-Ramus designed what looks like a four-level parking garage spiral for the books.

Mr. Prince-Ramus has been a visiting professor at Harvard, Columbia University, Yale and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). In 2011, the Huffington Post designated Mr. Prince-Ramus as one of the five best architects under 50 years old.

The redesign of 450 West 33rd Street will bring the building into the fold of Brookfield’s larger vision for Manhattan West. A public plaza will be created at the development to connect the new towers to the second floor east facade of the building, where retail will be added. Also, connecting to that public plaza is a new breezeway that will be built on the second floor on the West 31st Street side near 10th Avenue with stairs leading to street level. It creates access for pedestrians to walk directly through the block and the Manhattan West campus and is about a block from the High Line, serving as a sort of extension. Mr. Prince-Ramus also redesigned the lobby of the building with a modern, sleek look to match its exterior. Although it is an adaptive reuse project that will blend into the modern complex, Mr. Prince-Ramus hopes people don’t classify it that way.

“What would make me proudest would be if when the project is completed, hopefully they’ll just say it’s a really great building and hopefully they wouldn’t say that it’s a great adaptive reuse,” he said.