Commercial litigation—including foreclosure litigation—takes too long in New York. That happens mostly because of the discovery process, where the parties ask each other questions and request endless piles of documents, correspondence, experts’ reports and old email. All this information is supposed to help them prove their case, or help them realize they probably can’t.

Unlimited discovery may have been a good idea at some point. Thanks in large part to email, however, discovery has metastasized and mutated to a point where it often overwhelms the litigants and the courts, bogs down the process and costs way more than whatever value it produces.

The costs and other burdens of the discovery process themselves sometimes drive litigants to settle just to avoid sifting through thousands of old email messages, knowing that something somewhere in all that chit-chat written without legal advice will inevitably look bad to a court.

A few months ago, New York’s court system took what could become a meaningful step to speed up and simplify commercial litigation, at least for substantial commercial disputes such as defaulted commercial loans. That step consisted of establishing a new court rule on “Accelerated Adjudication,” which applies only in the commercial division of New York’s Supreme Court, the trial court for many commercial disputes.

The new rule, first effective earlier this year, applies only if the parties agree to it. Once the parties are in litigation, agreement seems unlikely. Thus, anyone negotiating a commercial transaction should seriously consider including “magic language” in the documents to have the new court rule apply if the transaction ever ends up in litigation in the commercial division.

The new rule is about a page and a half, with about a half dozen important changes in litigation procedure to speed things along. Some of those, such as a jury trial waiver, already appear in most transactional documents, and won’t matter much.

The heart of the new rule, though, consists of the severe new limits it imposes on the discovery process. For example, unless a party can show “good cause,” each side can conduct only up to seven depositions, each limited to seven hours. Other elements of the discovery process face similar limitations.

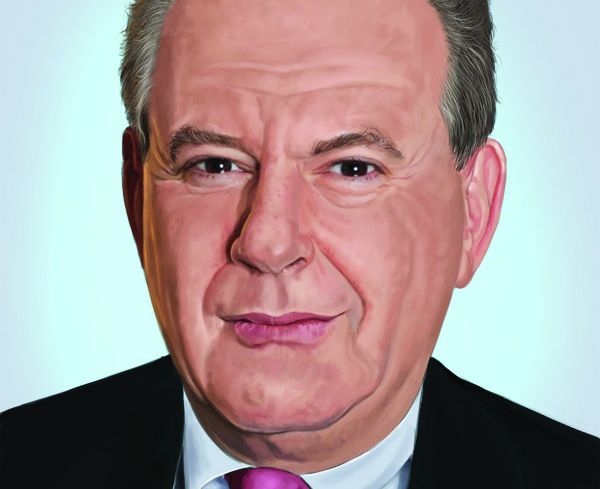

“It’s all designed to get the parties ready for trial faster and more economically,” said Richard Fries, a partner at Sidley Austin, who handles both lending transactions and litigation.

Any request for documents through the discovery process must be “limited to those relevant to a claim or defense in the action,” and of sharply limited scope. Those notions may sound obvious, but in fact they significantly narrow the previous scope of permitted discovery.

The new rule takes particular aim at the largest growth area of discovery—electronic discovery, the process of requesting and reviewing huge volumes of machine-readable information, such as email, documents and business records. The new rule says any e-discovery request must be “narrowly tailored” in identifying who must provide information. If the costs and burdens of a request are disproportionate under the circumstances, the court should deny it or require the requester to advance the cost of compliance. Again, these rather obvious propositions actually trim back the discovery process in important ways.

The new rule also seeks to speed along resolution of the case. First, the parties must finish discovery and other pretrial activities within nine months after filing a “request for judicial intervention”—the piece of paper that puts the case on the court’s radar screen. Second, the parties cannot appeal any court rulings until the case is over. This deprives defendants of their time-honored strategy of appealing practically anything at any time to achieve delay.

Commercial mortgage lenders, and other parties more likely to be plaintiffs than defendants in litigation, should probably update their documents to include the “magic language” necessary for the new accelerated adjudication rule to apply.

Conversely, borrowers may not be so keen on the new rule. Borrowers typically favor delay, unpredictability and procedural complexity—precisely what the rule seeks to eliminate or at least reduce. It would seem difficult, though, for any borrower to object in loan negotiations to an accelerated adjudication provision. How could a borrower, who wants the lender’s money, successfully argue that the borrower wants to preserve the maximum ability to torment and delay the lender, through endless discovery and other measures, if the loan ever goes into litigation?

Conceivably, of course, a lender could turn out to be the party that wants to appeal an interim ruling issued by the trial court, or conduct extended discovery about the borrower’s affairs. But that’s not likely. On balance, any party to a New York commercial transaction that wants to control the cost and duration of litigation should favor the new rule.

“The new rule has many good ideas in it,” Mr. Fries said, calling it “a noble and thoughtful effort to streamline commercial litigation.” He thinks it will speed up “certain kinds” of litigation, “especially mortgage foreclosures with relatively straightforward facts. That being said, we won’t really know how well the rule works, or whether cases can truly be resolved more quickly, until we’ve seen it in action for a couple of years.”

Joshua Stein is the sole principal of Joshua Stein PLLC. The views expressed here are his own. He can be reached at joshua@joshuastein.com.