Getting Along: Some Tips for Brokers and Lawyers

By Joshua Stein October 31, 2013 12:25 pm

reprints

Overheard in a broker’s office: “The lawyer is trying to blow the deal. There was an agreement, then the lawyer started raising all these problems. I don’t get half of them. Now I don’t know where this deal is going, except maybe in the ditch. I think the lawyer’s just running up fees.”

Overheard in a lawyer’s office: “The broker is just trying to get their commission as soon as they can. And it’s so much money! It makes our legal fees look like nothing. The brokers seem to think closing a real estate deal requires about as much thought as buying a loaf of bread.”

In some ways, the roles of broker and lawyer will inevitably collide, because each has different incentives and a different structure for payment. I’ve certainly seen that happen. And I’ve seen brokerage commissions at closing that dwarf the legal fees, even though the lawyers seemed to have done a lot more work for the deal. That perception, though, ignores the fact that the brokers worked for free on a dozen other deals that never came together, whereas the lawyers generally got paid by the hour—their full rate or something close to it—on those same other deals.

Handled right, the relationship between brokers and lawyers can not only be peaceful and constructive, it can also help both professionals do a better job for the benefit of their mutual client. It’s not very hard. Here’s how to do it.

Cooperation should start with the term sheet. From a legal perspective, a term sheet absolutely must say only about three or four things. The main event consists of making sure no one will face liability because they agreed to the transaction terms when they merely signed the term sheet. That disaster is relatively easy to avoid. It represents the threshold contribution that a lawyer needs to make to any term sheet.

Good brokers resist the temptation to try to make a term sheet “sort of binding,” a format that creates an unreasonable risk of trouble later, almost asking for tension between brokers and lawyers. A similar tension arises between getting a minimal term sheet signed to “lock in” the deal—at least in principle—and investing more time in the term sheet to try to head off issues that can consume lots of time and legal fees if they arise for the first time in the deal documents.

In loans, for example, it will often make sense for a lawyer to get involved in the term sheet, if only to try to raise and resolve important issues that don’t relate directly to pricing. Those issues could include, for example, scope of recourse liability, permitted transfers, and flexibility on leasing and alterations. It may take longer to handle those issues in the term sheet, but by doing so one can speed up and simplify the negotiation of loan documents later and prevent unpleasant surprises. One can also achieve a substantively better outcome by raising issues when the lender is in a competitive mood.

How about skipping the term sheet and “going straight to documents”? It sounds very forceful and decisive—a great way to get to the point and not screw around. It may speed things along for a while, but it will also often slow things down once the documents get issued. Misunderstandings that could have been cleared up quickly in a term sheet will ripple through the documents, requiring multiple changes and numerous negotiations—way more work than if the parties had invested more effort in the term sheet.

Even if the parties sign a thorough term sheet, similar tensions arise once the term sheet is in place and the parties want to move to documents. The attorneys never seem to distribute the first draft of documents quickly enough. Wouldn’t the deal move faster if we distributed something quick and dirty and then fixed it later? Not really.

Usually it will make sense to make sure that even the first draft of documents is complete and correct. That means allowing time for the principals, and broker, to sit down and read the documents and circle back with adjustments as appropriate. The broker need not read every word, just enough to make sure the documents properly capture the deal terms. Even though the lawyers are “supposed to” faithfully document the deal between the parties, sometimes they get it wrong.

Once the documents are out and the parties raise comments and find issues, the broker should stay involved. Often lawyers hesitate to compromise or drop issues. A good broker can help bridge those gaps, though it’s ultimately the client’s decision. But a lawyer who’s doing their job of identifying issues, and a broker who’s doing their job of trying to keep issues in proportion, can sometimes together help their shared client reach the best possible decision.

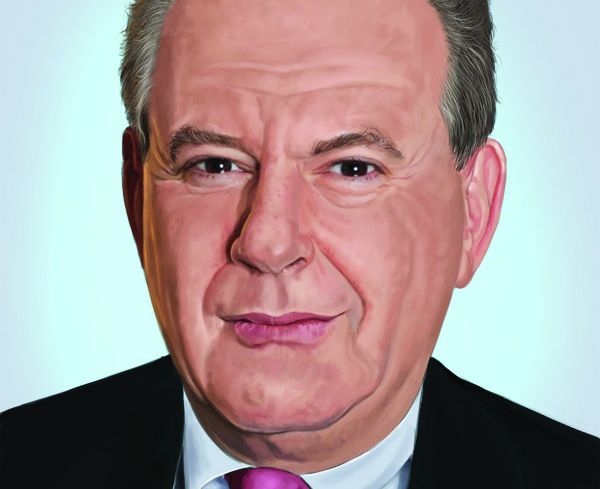

Joshua Stein is the sole principal of Joshua Stein PLLC. The views expressed here are his own. He can be reached at joshua@joshuastein.com.