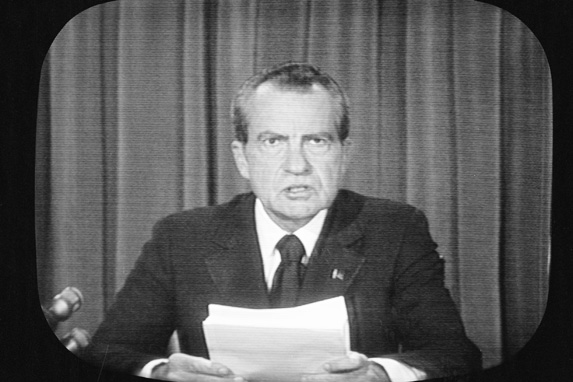

On June 17, 1972—41 years ago today—five men were arrested after breaking into the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate Hotel and Office Building at the Watergate Complex in Washington D.C. Two years later, U.S. President Richard Nixon had resigned.

The burglars would ultimately admit to having photographed documents and wiretapped phones during that incident and a previous burglary. While the details regarding how, exactly, the burglars were able to break into the building are murky, there was likely little more than physical locks and barriers—and a security guard—preventing their entry into the building.

The burglars would ultimately admit to having photographed documents and wiretapped phones during that incident and a previous burglary. While the details regarding how, exactly, the burglars were able to break into the building are murky, there was likely little more than physical locks and barriers—and a security guard—preventing their entry into the building.

It goes without saying that, four decades after the incident, the access control industry has come a long way. As such, The Commercial Observer caught up with Datawatch Systems, the company that currently provides access control and security services at that very same Watergate office tower, at 2600 Virginia Avenue, to see how much the industry has changed—and, the likelihood of a similar break-in at a government complex occurring today.

“If the latest technology is being utilized and the building is providing multiple layers of control, the chances are very, very small,” said Robert Dike, vice president of sales at the Bethesda, Maryland-based firm.

During the Watergate break-in, a security guard discovered the intrusion after noticing tape covering the latches on doors in the complex, which allowed the doors to close but remain unlocked. He removed the tape but found them re-taped an hour later.

“Prior to ‘74 there really wasn’t a lot of electronic control in these buildings,” Mr. Dike said. “Later in the 1970s, after Watergate, is when that really got jumpstarted. Access control came along to make sure that doors were unlocked and locked at preset times, giving you tracking ability to know exactly who was in the building and when.”

The building at 2600 Virginia Avenue no longer houses government entities, but Datawatch works with a range of them, from the DOJ to the IRS to the ATF to the DEA, and a long list of others, which to varying degrees have embraced technology that would make a Watergate-style break-in today nearly impossible because of the “layers of control” Mr. Dike described.

They include, but are not limited to, card readers in garages, perimeter doors, elevators and on entryways to individual floors and tenant spaces; external and internal camera systems; and a human component made up of guards.

Today’s motion-activated cameras also allow companies like Datawatch to send video clips to clients via the Internet anytime something—or someone—trips the system. Other tenants use smart phone applications to access buildings and unlock computers.

Others systems seem straight from the movies. Though used on a “limited scale,” some government agencies require biometrics, such as retinal scans and thumbprint-detection software, for movement within buildings; while Sensitive Compartmented Information Facilities are used as “safe rooms” for classified discussions.

Interestingly, however, New York City building owners are much less likely to utilize even the most basic access control when compared to Washington D.C.

“It’s dramatic the difference,” Mr. Dike said. “New York tends to use a lot of guards and less electronic control, and I think part of it is the federal government being in Washington D.C.”

“So the guards are obviously doing their job.”