Two Buildings, One Block: Andrew Roos on the Virtues of 28-40 West 23rd Street

By Daniel Geiger April 25, 2012 9:30 am

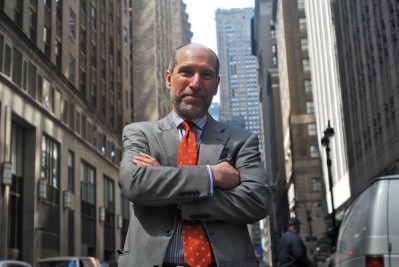

reprintsThe success of 200 Fifth Avenue has served in many ways as the template for 28-40 West 23rd Street, and no doubt many other buildings in Midtown South. The building’s developer, L&L Holding Co., guessed the popularity of the neighborhood and bet a big reinvention of the property would draw top-shelf tenants, a gamble that paid off when it landed Grey Advertising and Tiffany & Co. Now the landlord of 28-40 West 23rd Street is in the middle of a similar kind of makeover. The Cohen, Roos and Carmel families, who together own the 600,000-square-foot tower, have plans to create a roof deck and have done deals with tech companies that are invading the neighborhood in droves. After the jump, The Commercial Observer talks to Andrew Roos, a Colliers International leasing executive and an owner of 28-40 West 23rd Street. Return at 10:30 today for a second installment with David Berkey, L&L’s director of leasing.

The Commercial Observer: Why is 28-40 West 23rd Street a dual address?

Mr. Roos: The building is actually two combined properties—40 West 23rd Street was built in 1878 and the annex building, 28 West 23rd Street, was added onto it around the turn of the century. Forty is larger. It was the original Stern Brothers department store in 1878. Forty is a six-story building and 28 is a 12-story building, and the two together total about 600,000 square feet. One of the great things about the complex is the buildings were purposely combined—28 West 23rd Street was built as an add-on so the integration between the two buildings is seamless.

When did you acquire the property?

Around 1960—when we acquired it the building was used for mainly light manufacturing and showrooms. In the early 1980s, when the market became overheated in Midtown, that was one of the first times Midtown South really began to become redefined for creative firms that were looking to lower their occupancy costs.

Many of them fell in love with the architecture and decor. Forty is unique—it has a cast-iron facade, which is unusual north of Soho and Tribeca, where most of the cast-iron buildings are located. The building is not landmarked but the district is, the Lady’s Mile. It will never be torn down. It is a jewel and representative of the era in which it was built.

So the recent wave of tenants coming to Midtown South is not the first time the area has come into vogue?

Midtown South became a destination because of the architecture and ambiance of the buildings. The cost of these buildings today or even years ago made them impossible to replicate and this is not the first time that tenants have caught on to that. With this building we have broken one of the cardinal rules of real estate: we fell in love with the bricks. You should fall in love with the cash flow.

What work have you done on the property to help it gain popularity?

We first repositioned it in the mid-1980s. Jerry Cohen had a great idea, to take the open-air shaftway that is in the middle of the 40 building and put a large glass ceiling in to create an inner atrium. It was modeled after the Plaza Athénée hotel in Paris. We added French windows and flower boxes and restored the brick. There were beautiful wrought-iron balustrades. When the windows are open, it’s like being in a French hotel and it took away the burden of having a deep floorplate by connecting tenants to light and air.