It was something to be avoided. As America’s biggest foreclosure waiting to happen, Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village was viewed by the financial world as a $6.3 billion bet gone bad.

It was something to be avoided. As America’s biggest foreclosure waiting to happen, Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village was viewed by the financial world as a $6.3 billion bet gone bad.

David Tepper saw an opportunity.

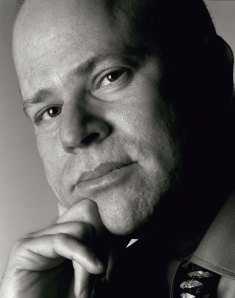

Founder of the high-risk–high-yield hedge fund Appaloosa Management, Mr. Tepper is the king of sniffing out the undervalued among the distressed, often realizing fantastic returns. After betting big on banks at their nadir in early 2009, he topped AR: Absolute Return + Alpha magazine’s list of the year’s top hedge fund earners, raking in an estimated $4 billion for himself.

Now, after buying more than $800 million worth of bonds that control Stuyvesant Town within the past year and a half—many of them risky—he is muddying up the giant foreclosure on the property, showing that he has no interest in watching from the sidelines. In late February, he filed legal action to steer the property in a new direction, in a bid to protect—or maximize—his investment, an action being fought by the special servicer organizing the foreclosure.

Whatever becomes of his case against the special servicer, which onlookers characterize as a long shot, Mr. Tepper’s involvement is telling of the curious, irresistible allure possessed by Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village, as it effortlessly coaxes waves of top financiers and real estate tycoons with its siren call.

Just as a 2006 sale caused the biggest names in real estate, equity and lending to aggressively climb over each other to throw billions toward the property, the distressed asset has brought out one of the biggest names of the distressed-asset world.

Mr. Tepper’s moves show that Stuyvesant Town, with its monotonous 56 red-brick buildings that may never house the rich and famous, is nevertheless still a crown jewel of New York real estate, over which everyone from the vulture fund manager to the third-generation real estate titan are eager to fight.

MR. TEPPER, 52, is something of an unassuming billionaire, offering a contrast with many of the others who swirl around Stuyvesant Town.

The son of a middle-class Pittsburgh accountant, he eschews ties, often wears jeans to the office and, notably, does not seem to have figured out just how to spend his money.

He has only one house, a modestly sized one in Livingston, N.J., that he bought for just $1.2 million two decades ago. He doesn’t own a private jet (he has a share), he has no yachts and his charitable contributions are limited. He has pledged $55 million to Carnegie Mellon, his grad school alma mater; and, other than that, his foundation’s tax filings show he has given away $2 million to $3 million a year to various food banks and other nonprofits. He did buy a piece of the Steelers football team, but only 5 percent.

With all that said, now that the last of his three kids is finishing high school, he says he is ready to start spending, at least a bit more.

“I tell my kids, when they’re all out of the house, I might decide to be rich,” he told The Observer last week. “My thing right now is, I want to get a vacation house to get the family to keep coming back home.”

Mr. Tepper rose to prominence in finance through various analyst positions and, in the 1980s, became a trader on the high-yield desk at Goldman Sachs, dealing with junk bonds. He was known for tremendous acumen.

“He’s a superb analyst,” said Richard Coons, now a managing director at Hexagon Securities, who worked alongside him in the Goldman years. “He never had anything on his desk except a 10Q, and he would look at a 10Q or 10k, and say, ‘Well, this is out of order, this is not right. This security is mispriced.’”

In 1993, after being passed over for partner at Goldman, he left to start Appaloosa, targeting high-risk assets that would, if successful, bring in fantastic returns.

They did.

Over the years, the funds he’s managed have grown from under $100 million to around $13 billion, as he has targeted many dying industries and businesses in bankruptcy, running toward an asset when everyone else is fleeing from it. He invested in Canadian steel. He was an investor in auto parts manufacturing giant Delphi and nearly came to control the company in 2008 before he pulled out of a $2.6 billion deal to buy it out of bankruptcy, a costly move.

And in 2009, after losing substantially in 2008, he bet big on Bank of America and Citigroup, when they were at their lowest, effectively a bet that the Obama administration would not take over the financial system. This strategy was central to his success last year.

FOR MR. TEPPER, Stuyvesant Town is another Bank of America. His interest in the property was piqued a bit over a year ago, after he began investing in commercial mortgage-backed securities, funds that slice up debt on an array of commercial mortgages and allow investors to buy up bonds with different levels of risk.

Throughout 2009, investors expected a default on the $6.3 billion deal, which had a $3 billion first mortgage and was considered a wildly flawed investment. Analysts looking at the current cash flows put its value at a shockingly low $1.7 billion to $2 billion. Investors were bearish on CMBS, flooding the market with bonds and driving down prices.

Mr. Tepper strategically began to scoop up specific slices of the CMBS trusts that contained Stuyvesant Town’s mortgage, many of which were at a great discount from their initial value. The purchases were a bet that the apartment complex wasn’t worth the low values that were being thrown around—a bet that the markets were overly pessimistic and that traders would eventually come around to seeing that.

“The idea of this thing being worth sub–$2 billion is just as ludicrous and ridiculous as the $6 billion price initially,” Mr. Tepper said. “The bottom line is, people were in pure panic mode, and we weren’t.”

So after a default by the owners in January, it came as a surprise to Mr. Tepper and Appaloosa when the special servicer responsible for figuring out what to do with Stuyvesant Town opted for a foreclosure. That could require two separate rounds of transfer taxes and other fees, Appaloosa has charged, perhaps costing $200 million—money that would otherwise go to the holders in the riskier slices of Stuyvesant Town investments. Mr. Tepper would prefer a bankruptcy and restructuring. In a foreclosure and sale, the holders of riskier slices of debt can be left completely empty-handed.