Subsidy City: The Real Public Costs of the World Trade Center Towers

By Eliot Brown April 5, 2010 5:34 pm

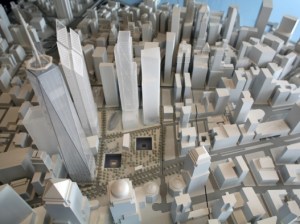

reprints For more than a year, an exhaustive battle raged over the future of developer Larry Silverstein’s towers at the World Trade Center, with the Port Authority, Silverstein Properties, the city and the state fighting over just what to build, and how to fill a financing gap.

For more than a year, an exhaustive battle raged over the future of developer Larry Silverstein’s towers at the World Trade Center, with the Port Authority, Silverstein Properties, the city and the state fighting over just what to build, and how to fill a financing gap.

And when a tentative deal was finally reached late last month, the result was one celebrated by many a public official: With new rent abatements, $600 million in other forms of public money, and conditions Silverstein would have to meet, the development of two towers could go forward, freeing the site from its potentially crippling deadlock.

But to take a step back from the specifics of the financing, the deal broadly represents the latest chapter in a recurring storyline at the site, as the quest to rebuild has repeatedly demanded new public assistance as the years have added up since 9/11, both for the infrastructure and for the private office towers planned by Silverstein.

Between subsidies, the assumption of risk, and various other incentives, a tally by The Observer counts 10 various forms of public assistance, each with substantial potential price tags. If it is fair to add these up—and there is a decent argument to say it is misleading to do so—the total risk is well over $2 billion.

While the ultimate public tab may never come to be that high, what is clear is that the amount of public assistance for what is now to be two private World Trade Center towers with 4 million square feet is exceptional, and far more than ever advertised or anticipated when the rebuilding plan was sold to the public.

Taken with billions in cost overruns on the site’s public infrastructure—including a PATH station for 60,000 commuters a day now estimated to cost $3.2 billion, up from $2 billion—it is an emblem of a flaw so common to public-private partnerships: One development plan is sold to the public with promises of a certain subsidy level and an expected long-term gain from rent. But conditions change, costs increase, the market worsens, and once it seems too late to turn around and scrap a deal, a developer needs more aid, and the public sector is in a tough place to refuse.

The latest agreement—in which the city, state and Port Authority will put in $210 million in equity, $390 million in less risky debt coverage and more than $400 million in rent abatements—is now the fourth layer of public assistance promised to get the private office towers off the ground. First there were tax-free Liberty Bonds; then a “Marshall Plan” meant to aid Lower Manhattan’s recovery, with special breaks for the World Trade Center; then a revised financial agreement that included two new leases that are far more than the government would traditionally pay for office space. At each point, the implication was that the market would not bring these towers up on their own, so the public needed to step in with aid to clear a path for construction. And at the discussion of each round of assistance, the decision to add on a new subsidy had some rationality, with officials saying they were too entrenched to start over and rethink the broader plan.

The site, of course, is laden with emotion and politics, and the desire to rebuild after a terrorist attack sets the site in a different category than the traditional public-private partnership. But in layering on the assistance at various different points over the past nine years, what is clear from the latest deal is that the total amount of public assistance is extraordinary and tremendous, and one wonders if the current plan would ever have gone forward had the public known its full contribution from the start.

Here is the list (with a disclaimer below):

-$2.6 billion in Liberty Bonds, first granted in 2002. This is financing that is exempt from federal, state and city taxes, with the federal government missing out on the bulk of the tax revenue that would have been created by traditional financing. No analysis of the estimated current subsidy—foregone tax revenues—on these bonds has been made available. But using the same ratio of total bonds-to-subsidy estimated for Yankee Stadium tax-exempt bonds would mean more than $600 million in foregone revenues. Liberty Bonds were used to help spur numerous other developments in Lower Manhattan, as well as the Bank of America tower in midtown.

-Commercial Rent Tax abatement, granted in 2005. This relieves tenants of a would-be 3.9 percent tax on their rent. Assuming a conservative $65 a foot—the rent for the Port Authority’s space in Tower 4—for the 3.4 million taxable square feet between the two towers, this would comes out to $8.6 million a year, or $129 million when added up over 15 years in forgone revenue to the city. The commercial rent tax was exempted for all of Lower Manhattan in 2005, although it was only temporary. The World Trade Center site was granted a permanent abatement. As the rents rise, the foregone revenue clearly increases (a Silverstein-commissioned report by brokerage CB Richard Ellis anticipates at least $91 a foot for Tower 2 in 2015).

-Direct rent subsidy, granted in 2005. This provides a $5-a-foot subsidy for the first 750,000 square feet leased at the World Trade Center, and would not necessarily go to the Silverstein towers. Given that the subsidy has already been earmarked for a 290,000-square-foot lease at 1 World Trade Center, the most the tenants in the Silverstein towers could receive is for 560,000 square feet, which would come out to $42 million over 15 years.

-City of New York lease option on 582,000 square feet in Tower 4 at $56.50 a foot, granted in 2006. While Silverstein has argued this lease is below market for new office space, the city traditionally leases older office space at substantially less cost, often in even lower cost locations such as downtown Brooklyn and Long Island City. Assuming an average of $44 a foot for Lower Manhattan Class A office space that would increase to $49 a foot by 2013, this would be a total additional cost to the city of $65 million over 15 years. (Silverstein has emphasized that its buildings are more efficient than older buildings, and thus provide additional benefit). The lease option was negotiated in the context of the realigned financial agreement from 2006 in which the Port Authority assumed the right to develop 1 World Trade Center and another development parcel across from the site.

-Port Authority lease for 600,000 square feet in Tower 4 at $65 a foot, tentatively granted in 2010. Taken with the same assumptions as the city, this comes out to $144 million added up over 15 years. This was initially agreed to in 2006 as well, although the rent was increased in the latest agreement.

-City and state equity in Tower 3, tentatively granted in 2010. The city and state have agreed to put $210 million in equity for construction of this tower should Silverstein secure a prelease of at least 400,000 square feet at $60 a foot and raise $300 million in private capital. The city money is from payments in lieu of taxes the city would not receive if there were no tower.

-Public backstop on Tower 3, tentatively granted in 2010. The Port Authority, city and state governments have agreed to put in $390 million to pay debt service on a $1.1 billion loan for Tower 3, should the rents from the tower prove insufficient to service the loan. This money would only go to service the debt after exhausting about $200 million in additional Silverstein funds (from insurance money meant for Tower 2 and trapped fees and proceeds).

-Partial rent abatement for Tower 3, tentatively granted in 2010. The Port Authority has agreed to partially abate the rent for Tower 3, with Silverstein paying 25 percent rent until tower construction (when it would increase to 50 percent rent). At 10 years of 25 percent rent, this would come out to, roughly, $195 million. (The actual number may be higher; the Port Authority would not provide a specific estimate.)

-Rent abetment for Tower 2, tentatively granted in 2010. With the construction date for Tower 2 pushed to the indefinite future, the Port Authority plans to grant a full rent abatement for 10 years for the tower. This comes out to roughly $260 million (The actual number is likely higher; the Port Authority would not provide a specific estimate here either.)

-Backstop on Tower 4 loan. The Port Authority will back the debt on a $1.3 billion loan for Tower 4. Given that there are two government tenants (including the Port Authority) for 1.2 million square feet, it is highly unlikely the agency would ever pay this loan off in full.