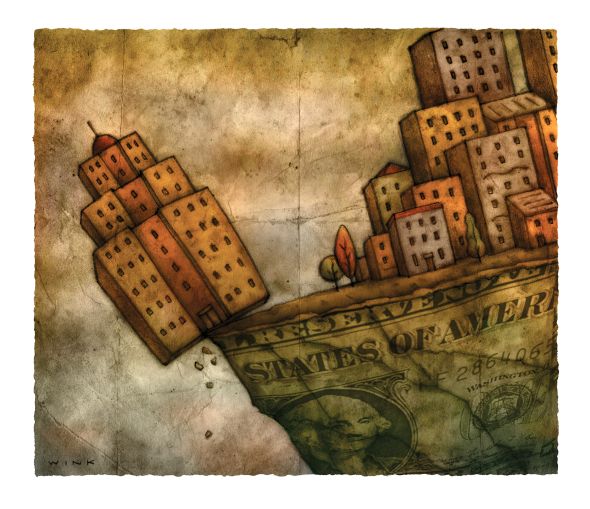

Have Investment Sales Finally Fallen Off a Cliff?

2019 is looking like the year investment sales finally fell off a cliff. Now what?

By Adam Bonislawski November 6, 2019 10:54 am

reprints

When, years hence, poets sing of the golden epochs of New York’s commercial real estate scene, 2019 will not be among them.

Investment sales definitely took a dive this year. Through August, total transaction volume was down 26 percent and total dollar volume was down 25 percent year over year, according to numbers from Cushman & Wakefield (CWK).

Like any shift in the market, a variety of factors are at fault — global economic uncertainty, unrealistic seller expectations, especially attractive debt markets boosting the allure of a refinance — but if the city’s property market cognoscenti are to be believed (and why wouldn’t they be?), nothing has loomed so large as the raft of new rent laws passed by Albany at the beginning of the summer.

The laws feature a number of changes that will likely impact the profitability of rent-stabilized buildings throughout the city, including the elimination of provisions that allowed owners to deregulate units once their rents and their tenants’ incomes hit certain thresholds, and a decrease in the rent hikes landlords can charge to cover capital improvements.

The numbers back up the notion that the rent laws are substantially to blame for 2019’s slow investment sales market. While overall sales volume is down 26 percent, multifamily sales volume is down 35 percent, said Nishant Shah, an associate director at Cushman & Wakefield. And, if you strip out the multifamily market, sales volume for the remainder of the market is down 13 percent — not a great number, but not especially striking given the run-up in recent years, he noted.

“What we saw in 2014, 2015, 2016 was just unprecedented historically,” Shah said. “Those were some of the biggest years commercial real estate has ever had. I don’t think the pace we saw in those years was sustainable.”

Positing, then, that the sales cooldown is largely a story about the multifamily market, what can a person expect moving forward? A long-term deep freeze? A slow and gentle thaw? Depends on who you ask.

Pierre Debbas, managing partner and founding member of real estate law firm Romer Debbas, predicted that if the rent laws continue in effect as written, the city will see significantly less investment in the multifamily market.

“Every owner, investor, landlord we are talking to, they don’t see how they are going to continue investing in New York under the current parameters of the law,” he said. “The ones that were investing here are going to start looking in other markets.”

Debbas suggested that given the limited ability of landlords to raise rents under the new laws, multifamily properties had become essentially fixed-income investments.

“You’re making real estate into a fixed-income asset, but with the headache of actually being a landlord and having to deal with tenants and the upkeep of the building,” he said. “Why not go buy a bond and just sit tight instead?”

Andrew Sasson, a managing director at Ackman-Ziff, sounded equally pessimistic regarding the current market.

“The multifamily market is as shot as I have ever seen it,” he said, noting that, previously, rent-regulated buildings “were the ones that were flying off the shelf because they were what was seen as having the biggest opportunity. They had really low rents and you could go in there and either buy a tenant out or, if they moved, take the apartment over and increase the rent.”

No longer.

Sasson said that he expected things to loosen longer term. However, he noted that, given the time horizons of many multifamily owners, that process could take a while.

“These types of apartment buildings are usually owned by families for generations,” he said. “Unless there is a really big circumstance that is pushing it — a death or a divorce or some type of event in the family — they are willing to wait. Some of them are like, we don’t even want to talk about a sale for the next five years.”

There’s a noticeable lack of comparable sales that’s keeping buyers on the sidelines, said Shaun Riney, senior managing director of investments at Marcus & Millichap (MMI).

“We may have gotten certainty on the new [rent] laws, but one of the other things that freezes a marketplace is the lack of comps,” he said. “And in the immediate aftermath [of the rent law changes] nobody knows what the true market is. Without comps it’s very difficult to sell an investor on what the exit strategy looks like … and so it’s really hard to model anything.”

For now, owners still have a good shot at refinancing their properties, Sasson said. Without comps, banks don’t have the data to support drastically lowering reappraisals of regulated multifamily properties.

“[The refinancing] market is going to be very robust,” he said. “Until banks and appraisers start viewing the value of these buildings the way investors are, it’s going to be very robust, because rates are low.”

Riney said he expected to see some turnover in the investor ranks as buyers with models based on the old rent laws move out and a fresh set of buyers come in.

“We’re in a period of time where the old buyers are cycling out and new buyers and new capital formations are being constructed,” he said. “New partnerships, new sources of money coming together based upon the new rules that are now in place.”

He compared it to the years following the 2008 crisis where, he said, “many of the people who were buying in 2010, 2011, 2012, were different characters from those who were buying in 2005, 2006, 2007.”

“I’m having a lot of conversations with new [investor] groups right now, trying to educate them on the market,” Riney said. “They have fresh capital and they don’t have the baggage of legacy assets that are hobbled with old pricing.”

Cushman & Wakefield’s Shah said he expected “that, relative to what we saw during the peak in 2014 and 2015, you’re going to see mostly people who are just looking for steady cash flow.”

“A lot of the upside has been taken away [from multifamily] by the fact that you can’t convert rent-stabilized units to market rate,” he said. “So now what you’re looking for is kind of planting your money into the building and hoping for a steady, predictable cash flow.”

Victor Sozio, an executive vice president at Ariel Property Advisors, echoed Riney’s comments, noting that he has seen new sources of funding begin to move into the market in the months after the rent laws passed.

“A lot of the operators who were very active in the past few years told me right after the legislation passed that unless [a property offered] a 7 percent cap rate going in, they just didn’t see how they could buy anything,” he said. “Fast forward a few months later to September, and some of those same operators have hooked up with different capital that is viewing this as their chance to come in and be competitive. And those same operators who were telling me they needed a seven cap in July are now ready to secure something at six.”

Whether owners are ready to sell at that price remains another story, though, Sozio said. “A lot of sellers haven’t reconciled themselves yet to that type of pricing, because they were dealing in a market for years where that would have been a very cheap price for a buyer to pay.”

Here the difficulties facing the multifamily market come into alignment with those afflicting the city’s commercial real estate business writ large.

“There’s a real disconnect between buyers and sellers as far as pricing,” said David Sturner, president and CEO of MHP Real Estate Services, speaking not only of the multifamily market but the retail and office markets, as well.

As Ackman-Ziff’s Sasson noted regarding the multifamily market, Sturner suggested favorable refinancing rates were likewise allowing owners in other parts of the commercial sector to hold onto their properties in hopes of ultimately getting their price.

“Sellers are finding that with the disconnect on pricing, refinancing is the way to go, especially with rates as low as they are,” he said.

Beyond those factors, Sturner cited the general environment of uncertainty, calling the current moment “probably the most uncertain time we’ve been in, certainly in my lifetime.”

That might seem an overstatement to anyone who remembers 2008 and its aftermath, but Sturner said that while that period certainly had its challenges, most everyone could at least agree on what those challenges were.

“As much as [in 2008] everyone was dealing with a real change in our business, everyone I think was prepared for it and knew it was going to be a long trail back,” he said. “Right now, there are just so many differences of opinion with regards to the next recession — when, if, and how big.”

“There are certainly people sitting on the sidelines that do have capital to deploy but who are finding it difficult and are willing to wait for the correction,” he said.

One event on the horizon that could help break up the current logjam is debt coming due on properties purchased at high prices during the hot market of several years ago, Sozio said.

“If you look at how active the market was in [2015] and [2016], the pricing was pretty frothy, and a lot of those purchases were secured with five- to seven-year debt that will be coming up in the next one to three years,” he said.

There’s also a measure of optimism among multifamily investors that the new rent regulations will be reversed, at least in part, either via lawsuits (in July, a group of landlords and trade organizations filed a suit in federal court challenging the legislation) or a change in the political landscape. Until these hopes come to fruition, however, they are just as likely to reinforce the current stasis as they are to grease the wheels of commerce.

Multifamily owners “think that, given their timelines, they’re going to survive certain political terms, and in surviving those terms, they think the pendulum is going to swing back in their direction at least a little bit,” Sasson said. “It might not be completely, it might not be 50 percent. It might be 20 percent, but even that 20 percent is better than where they are.”

Given that outlook, those who don’t have to sell aren’t rushing to. At the same time, the assumption that the rent laws are unlikely to remain in their current form could lead some buyers to take the plunge, Riney said.

“If I have to choose between an equal cap rate in a tertiary or secondary market versus New York City, maybe I do want to take the chance that these laws will collapse under their own weight,” he said.

And, even if the rent laws themselves don’t change, the city’s Rent Guidelines Board could help landlords by approving larger annual increases, Riney suggested. In fact, during Crain’s New York’s recent housing forum, Housing Preservation and Development Commissioner Louise Carroll hinted at just such an outcome.

“New York City is the most resilient marketplace in the world,” Riney said. “If you did this type of stuff in most cities, everyone would run to the hills. But there’s always going to be a buyer in New York City.”

Not everyone shares this outlook, though.

“The clients I’ve talked to — fund managers, family offices, individual investors — it’s either a combination of just keeping their cash in the bank and waiting to see what happens, or they are leaving New York and going into other markets,” Debbas said. “New York City isn’t the only place that’s a safe and profitable investment in America.”