High-Priced Rent Forces New Yorkers to Self-Store in Outer Boroughs and Beyond

By Juliette Fairley September 30, 2015 1:00 pm

reprints

When Samuel Rosen visited his girlfriend’s self-storage unit in Manhattan, he had to climb over boxes to find items for her.

“It wasn’t user-friendly,” Mr. Rosen told Commercial Observer. “I hated not knowing what was inside each box in the storage unit and having to visit the storage facility to retrieve things.”

As a result, Mr. Rosen launched MakeSpace three years ago, a white-glove self-storage company that employs drivers to pick up and drop off customer’s possessions to and from a warehouse that’s located in New Jersey.

“Traditional storage is inconvenient but MakeSpace is the next generation of user-friendly self-storage companies,” said Mr. Rosen whose company is growing up to 30 percent month-to-month.

Overall, self-storage has been the best-performing asset class in commercial real estate by average total returns, including dividends over the last 15 years, according to data from National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts.

“The growth from self-storage [real estate investment trusts is] surpassing all other REITs and most self-storage companies are privately owned,” said Jason D. Meister, a vice president and broker with Avison Young. “There’s a lot of opportunity to expand and invest.”

The demand for storage coupled with rising commercial rent prices in Manhattan are forcing self-storage operators to the outer boroughs and neighboring states.

“Owners and operators are absolutely going to the outer boroughs to create storage outlets because storing is not the highest and best use of commercial real estate in Manhattan, so they are seeking sites in submarkets like Sunnyside and Glendale in Queens,” Mr. Meister said.

In March, Treasure Island acquired a 100,000-square-foot industrial building on Cooper Avenue in the Glendale area of Queens for $7 million. It formerly served as a meat processing plant, which the new owners are converting into self-storage.

“The strong demand indicates that Manhattan residents would rather store their stuff than move out of the city or pay more rent for a larger apartment,” Mr. Meister said.

MakeSpace, for example, operates like an extra closet.

“A customer should never have to visit their storage unit or forget what’s in it,” Mr. Rosen said.

That’s why MakeSpace customers pack up green bins that scheduled drivers provide for them. The contents are then catalogued, stored and listed on the MakeSpace website. Clients can log into and review the contents and decide when they want MakeSpace drivers to deliver specific items from the New Jersey storage warehouse.

“Traditional self-storage units are usually located in the outskirts of cities, which can be remote and inaccessible,” Mr. Rosen said. “Our customers enjoy the door-to-door convenience our service provides, as well as the online catalogue that keeps belongings organized and accessible at just a click of a button.”

Securing a suitable piece of land in the outer boroughs of the city or a neighboring state doesn’t make launching a storage facility much easier.

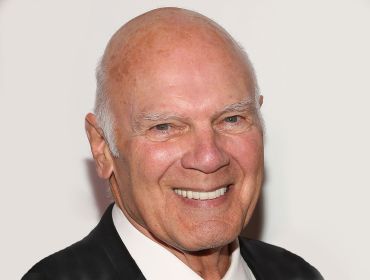

“It takes three years to reach stabilization,” said Dean Jernigan, the former chief executive officer of CubeSmart and current CEO of Jernigan Capital, both of which trade on the New York Stock Exchange.

That’s because financing the acquisition and development of a storage facility can be especially challenging.

“Traditional lenders are staying away from storage development because there is no pre-leasing and the bank has a large reserve requirement to meet current banking regulations,” Mr. Jernigan said.

Enterprising self-storage companies are even offering drive-through service.

“You pull up, punch in a code and the gate opens,” said Andrew Maguire, an attorney in Pennsylvania who represents a publicly-traded REIT that owns and operates self-storage facilities in numerous states.

Investors flock to the sector because self-storage facilities are a strong asset class. “The demand from self-storage investors results in REITs dedicated to acquiring these assets,” said Mr. Meister.

There’s also better lighting in some storage buildings, plus online bill payment and a front desk that’s staffed at least part time in more posh facilities.

“Many of the operators are now offering ancillary business services, such as packing and shipping, moving and organization, customized racking systems, as well as providing flexible office work space for mobile small business operators,” said Jim Berry, a managing member of RRB Development in Atlanta.

Such operators include CubeSmart and Treasure Island.

“Treasure Island is including a retail component at [its] new Queens location where clients can box, tape, ship and receive their belongings,” said Mr. Meister.

Financing for self-storage developers is generally available with equity requirements between 10 percent and 40 percent of the total development costs for a project, according to Mr. Berry.

“Recent demand has caused actual lease-up periods to be significantly shorter time periods than the underwritten three-year period, and, in some cases, stabilized occupancy has been achieved in less than 12 months,” Mr. Berry said.

Capital to launch a new storage facility is used to fund pre-development, construction and operational costs that include design, zoning, permitting and land acquisition.

Traditional storage companies, such as Manhattan Mini Storage, Gotham Mini Storage and NYC Mini-Storage, have long discovered another way to profit off their clients who are often hoarders or clutterers, a compulsion that involves collecting a never-ending array of various household items. (It costs as low as $30 per month at Manhattan Mini Storage.)

“People leave their things in these storage units over time and pay for it to sit there for years and part of the self-storage business is eventually liquidating what’s in these storage facilities and pocketing the proceeds when a customer stops paying and abandons the storage unit,” Mr. Meister said. “Liquidating the content of the storage unit isn’t the main driver of the business. It’s just a little extra.”

Companies like Roost.com are taking the collecting habit to a whole new level by offering Airbnb-type listings for people who will rent a portion of their garage or even a room in their spacious suburban homes to neighbors in need of storage space.

“People have a strange relationship with their belongings,” Mr. Maguire said. “They will go to any lengths to hold onto them until they are ready to let go even if it’s a bunch of books they’ve already read through once.”

But new generation storage facilities are raising the bar. Mr. Rosen claims MakeSpace’s Manhattan clientele isn’t storing for the sake of collecting dust and no customer actually visits the storage warehouse. “Who wants a storage development next to their luxury building?” he asked.

Some 40 percent of MakeSpace’s Manhattan customer base report they wouldn’t otherwise use traditional self-storage companies, which could be a real indicator that valet self-storage companies like MakeSpace are growing the market share of people who use storage outlets.