Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (FMCC) returned to the spotlight last week when the Federal Housing Finance Administration announced on Wednesday that it had directed the government-sponsored enterprises to delist their common and preferred shares from the New York Stock Exchange. The GSEs will likely trade on the over-the-counter market and will maintain their registrations with the Securities and Exchange Commission. They will both continue to file quarterly S.E.C. statements.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (FMCC) returned to the spotlight last week when the Federal Housing Finance Administration announced on Wednesday that it had directed the government-sponsored enterprises to delist their common and preferred shares from the New York Stock Exchange. The GSEs will likely trade on the over-the-counter market and will maintain their registrations with the Securities and Exchange Commission. They will both continue to file quarterly S.E.C. statements.

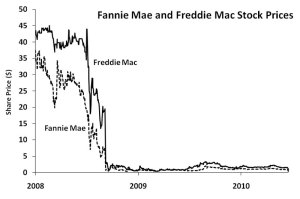

The F.H.F.A.’s move followed a notification from the exchange that Fannie Mae (FNMA) had fallen out of compliance with its minimum trading price guidelines. The GSEs’ stocks have continued to trade since they were seized by the federal government following a plunge in their share prices two years ago. In the time that has followed, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have received $145 billion in public support in the form of Treasury investments in senior preferred shares.

What Does the Delisting Mean?

In reporting on the implications of de-listing for the future of the GSEs, The Financial Times intimated that it would “pav[e] the way for a broad overhaul of the large government-controlled US mortgage finance companies.” But the F.H.F.A.’s own characterization of the delisting suggests something less than a watershed event. In last Wednesday’s press release, the acting director of F.H.F.A., Edward DeMarco, stated that the agency’s directive “does not constitute any reflection on either Enterprise’s current performance or future direction.”

In stating that the delisting decision was “related to stock exchange requirements for maintaining price levels and curing deficiencies,” Mr. DeMarco does concede that the government does not view a cure as sustainable. Alternatively, the government does not view the required expenditure of resources as being in the public interest. And so the delisting “simply makes sense and fits with the goal of a conservatorship to preserve and conserve assets.”

As for common shareholders who stand to lose from the delisting, investment in the GSEs during conservatorship and concurrent with their extraordinary losses was necessarily fraught with market and political risk. This outcome was fully anticipated by a wide range of investors and market analysts, who have assumed that the net worth of the GSEs would remain negative until a fundamental restructuring wiped out legacy shareholders.

The F.H.F.A.’s signaling error in allowing the shares to trade during the conservatorship would only allow the most risk-seeking shareholders to assume an implicit guarantee of value.

What Does It Mean for Multifamily Financing?

The GSEs’ multifamily portfolios continue to perform, exhibiting measurably lower default rates than securitized and bank multifamily pools. In part, this reflects the supportive risk-sharing arrangements of programs like Fannie Mae’s DUS. The serious delinquency rate for Fannie Mae’s multifamily loans was 0.8 percent as of March 31, up from 0.6 percent in the previous quarter and 0.3 percent a year earlier.

While increasing, the absolute measure is still only a fraction of the default rate for bank and CMBS multifamily loans. At Freddie Mac, the 60-day delinquency rate was 0.2 percent as of March 31. The 90-day delinquency rate was less than 0.2 percent.

Given the exceptional performance of Fannie Mae’s and Freddie Mac’s multifamily businesses, one might expect that these activities will remain untouched. Add to that, the GSEs are unique as a class of lender in consistently making new multifamily mortgages over the course of the credit crisis.

Even in the first quarter of this year, the GSEs’ multifamily mortgage holdings increased by $20.1 billion at a seasonally adjusted annualized rate. Agency- and GSE-backed mortgages pools accounted for another $3.3 billion annualized increase. Otherwise, private pension funds increased their annualized net lending by $1.1 billion; all other groups were essentially unchanged or retreating.

Apart from the relative health of the GSEs’ multifamily lines of business and the important role that the GSEs play in supporting credit availability outside the largest markets-in the largest markets, such as New York, there is evidence of inefficient and undesirable crowding out of bank lenders-the broader context for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac remains a function of their single-family business losses. These losses are expected to persist, necessitating an extended period of conservatorship or other form of support. And as long as the issue of the GSEs’ long-term structure and mandate remains in flux, the question of their ultimate role in the multifamily business remains unanswered.

The pending delisting of the GSEs may, in fact, help to ease some of the near-term challenges that they currently face in being answerable to both public policy makers and to stockholders. Inasmuch as the delisting allows them to focus on satisfying the specific goals laid out for them by policy makers, it offers an additional degree of freedom to focus on those goals while working toward long-term viability under some new structure.

As for what that new structure will be and how it will impact the giants’ multifamily activities, the delisting offers no new insights except in further clarifying that public shareholders will certainly not be party to the decision-making process.

schandan@rcanalytics.com

Sam Chandan, Ph.D., is global chief economist and executive vice president of Real Capital Analytics and an adjunct professor of real estate at Wharton.