Despite Surprisingly Brisk Fire Cleanup, L.A.’s Recovery Risks Hitting a Wall

Public and private efforts sparked a months-long wave of clearing that now might be running out of energy

By Nick Trombola September 12, 2025 11:16 am

reprints

On Jan. 8, the day after the Los Angeles fires exploded and ultimately consumed most of Altadena and the Pacific Palisades, Paragon Commercial Group co-founder Jim Dillavou’s parents and sister lost their homes.

Dillavou’s parents, both in their 80s, managed to fill a car full of belongings before the Eaton Fire ravaged their Altadena neighborhood. They were lucky — Dillavou’s sister and her family escaped the Palisades blaze closer to the coast with only the clothes on their backs.

“The only word that really comes to mind is ‘surreal,’ ” Dillavou said. “We’re from California, we’ve spent our entire lives here, and we joke that we’re very well prepared for an earthquake. But at no point in time did we think that 40 miles apart, on the same day, that two houses would burn down in a fire that was never on the radar. I think that’s the definition of a black swan event.”

It took nearly four weeks — plus 1,400 fire engines, 84 aircraft and thousands of firefighters hailing from nine states, Canada and Mexico — to fully contain both fires, which were spurred by 70 mph Santa Ana winds. By the time that the flames were finally beaten back, they had together killed 31 people (though estimates of indirect deaths range far higher), destroyed more than 16,000 structures, and caused upward of $160 billion in property and capital damage. The fires were among the most destructive, and costly, extreme weather events in American history.

Trauma caused by the events still lingers for many, and likely will for the foreseeable future. But the collective response from the L.A. community, particularly in the early months of the region’s recovery, was electric. A massive cleanup effort, led by the Army Corps of Engineers and local, state and federal agencies, kicked off almost immediately; a deluge of nonprofit organizations formed to coordinate the flood of financial, material and time donations; certain construction regulations were, at least ostensibly, eased to cut red tape; and everyday Angelenos fed and housed neighbors, fostered displaced animals, and spent their free time mobilizing supplies.

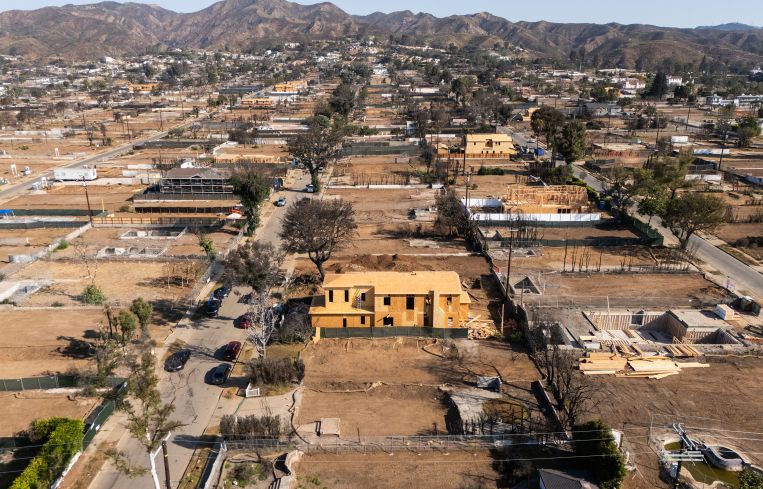

Eight months have passed since the fires began, and, for most, life goes on in Southern California. Yet the recovery effort for Altadena, Malibu and the Palisades is far from over — if anything, it’s only just begun. And the challenges posed by the recovery’s later phases are likely to only intensify in complexity, financial burden and time spent, rather than the opposite.

“We’re at an inflection point, which is, for the most part, the debris has been cleared, save for some of the commercial areas in both regions,” said Nick Geller, managing director of nonprofit Steadfast LA. “And now what?”

What has worked

Despite the sheer scale of the disaster, the cleanup effort has made remarkable progress. By early July, six months to the day after the fires began, Gov. Gavin Newsom declared that the debris removal program was largely complete, months ahead of schedule. It may have been the second-largest wildfire cleanup in state history behind the 2018 Camp Fire, yet, according to the governor, the L.A. fires cleanup was the fastest ever of any major disaster nationwide.

Crews led by the governor’s Office of Emergency Services and the Army Corps of Engineers, alongside the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the city and the county of L.A., have collectively removed over 2.5 million tons of debris, ash, concrete, metal and contaminated soil from the burnt areas — double the amount of refuse removed from Ground Zero in the wake of 9/11, according to the governor’s office.

If anything, some experts and residents have questioned if the cleanup has progressed too quickly, at least regarding concerns about long-term soil contamination or cases of cursory rehabilitation. Yet, in general, support for the cleanup at every governmental level — including from President Donald Trump — supercharged a process initially projected to span up to 18 months.

“I chalk it up to two things,” said Anish Saraiya, director of Altadena recovery for the L.A. Board of Supervisors. “One, strong support from the federal government. They definitely equipped both the EPA and the Army Corps with the resources they needed to scale up and attack something of this size and scale. The other part of it was coordination at the local level.

“Ultimately, the Corps and the county needed [each property owners’] approval to go onto [their] property to clear it. So we had to get 6,000 property owners [in Altadena] to sign up through this system. … And, you know, ultimately, everybody who initially thought that this would be a very slow program and wanted to do it themselves, a lot of them ended up saying, ‘Actually, we’d really like it if the Corps could come in and clear our properties too.’ So coordination across all levels of government was a really key part of it.”

As the cleanup effort began to take shape, the private sector wasn’t content to sit on its hands.

Real estate magnate and former L.A. mayoral candidate Rick Caruso in February launched Steadfast LA, a nonprofit coalition of private sector and civic leaders aimed at collaborating with local authorities to cut red tape, coordinate communication between the dozens of various entities involved in the recovery, and support innovative rebuilding solutions. The coalition, which includes CBRE President of Advisory Services Lew Horne, Banc of California Chairman and CEO Jared Wolff and Netflix CEO Ted Sarandos, has so far settled on four core initiatives: expediting the rebuild permitting process via AI-driven software; providing financial help for families to build modular housing; cultivating a public-private partnership with the city to rebuild public infrastructure (so far in the form of restoring the Palisades Park and Recreation Center); and launching a $1 million grant program for small businesses affected by the blazes.

Regarding the first initiative, Steadfast LA and LA Rises — a fellow private-public recovery coalition led by L.A. Dodgers Chairman Mark Walter and basketball legend and real estate investor Magic Johnson — partnered with software firm Archistar to fast-track the development of an AI tool aimed at facilitating home rebuild permits. The tool, currently freely available for both City of L.A. and L.A. County residents, scans permit applications for noncompliance issues before the application is sent off for approval, potentially saving weeks of bureaucratic headaches.

L.A. County has received 1,838 rebuild applications within its fire-affected areas, as of Sept. 12, ranging from single-family residences, to accessory dwelling units, repairs and other accessory structures. To date, the county has approved 352, according to the county’s permitting progress dashboard. The city has so far received 1,393 applications for 782 unique addresses in the Pacific Palisades, with 521 permits issued for 314 unique addresses, according to its own progress dashboard.

Before the fires, county application approvals could average eight to nine months, Saraiya said, but now the county claims that it approves new residential applications within 71 business days on average. Palisades rebuild applications are now being approved nearly three times faster than typical single family home permits, a spokesperson for the L.A. mayor’s office told Commercial Observer.

As for the latter initiative, Steadfast and the Banc of California earlier this month announced the first tranche of small business grants, together totaling $125,000. Webster’s Community Pharmacy, Fair Oaks Burger and Altadena Cookie Company, all located in Altadena, are the initial three recipients, though over 500 applications have so far been submitted for the grants and more awards will be distributed in the coming days, per Steadfast.

While much of the recovery effort has focused on cleaning up debris and rebuilding homes, bringing commercial properties and retail businesses back online is just as important to making a community feel whole again, Steadfast’s Geller told CO. Indeed, for that very purpose, Caruso intends to reopen Palisades Village plaza in August next year.

It’s a sentiment shared by Dillavou, who was involved in drafting the Urban Land Institute’s Project Recovery report earlier this year, and provides volunteer advisory services to commercial owners impacted by the blazes.

“This is going to sound esoteric, but it’s true: Communities are built around retail,” Dillavou said. “Whether that’s a grocery store, or a local pub, or a mom-and-pop hardware store, like on Northlake Avenue in Altadena, or a local restaurant. These are the types of venues that create a sense of community, and the sense of community that people lost and want back. … We need to incentivize the retail to rebuild, because that’s going to incentivize the residential, and vice versa.”

Other nonprofits founded in the wake of the fires, such as LA Strong Foundation, are more concerned with day-to-day needs. Founded by husband-and-wife venture capitalists Drew Koven and Maxine Kozler Koven, LA Strong Foundation says it has coordinated the delivery of tens of thousands of units of essential goods, such as food, diapers and hygiene products, as well as facilitating services and resources to people on the ground.

Drew Koven, who is studying to become a rabbi, said that along with his experience in “simplifying complexity” as a venture capitalist, he felt a spiritual push to do something real after the fires.

“We recruited people who understood the sense of urgency, and that we’re not about bureaucracy, we’re here to get stuff done,” Koven said. “Call and you’ll get us on the phone; email us and we’ll get back to you. If we can’t help, we’ll direct you to partners who are better set up for the type of support you need. We built a network of nearly 50 partners, so we consider ourselves like a Swiss army knife. If you need a spoon, we know where to get the spoon, so to say. That’s our whole strategy. It’s a sharing, coordinated model where we’re better off together, all-for-one L.A.”

These organizations and initiatives have been critical in setting the foundation for the recovery yet to come. Still, experts warn that, if anything, the past eight months have been the easy part. The financially onerous and time-consuming nature of challenges on the horizon have the potential to stall, if not derail, rebuilding efforts if morale falters.

What challenges lay ahead

Steve Soboroff, the real estate developer and former L.A. police commissioner chosen earlier by Mayor Karen Bass as the city’s temporary chief recovery officer, succinctly described the weight of these problems in his April report to Bass.

“As the Army Corps of Engineers begins the process to complete their mission and the recovery reaches a new phase, our concern is that the current momentum and feeling of optimism could easily give way to extraordinary challenges that could seriously impede the rebuild and recovery effort,” Soboroff and his deputy, Randy Johnson, wrote at the time.

Soboroff’s bellicose, and well-publicized, departure from the role after its 90-day window was indicative of the first challenge: clear communication and coordination between recovery entities and residents. By the time of his exit, Soboroff claimed to have been hamstrung in his role, finding himself in the dark about major recovery plans such as Bass’s decision to reopen the Palisades to the public in late January (on which she ultimately backtracked a few days later) and confused about what the city actually wanted out of his appointment.

“They haven’t asked me to do anything in a month and a half, nothing, zero,” Soboroff told the Los Angeles Times in April. Soboroff did not respond to a request to comment about the recovery effort in the months since his exit.

But Soborff’s departure is old news, as are, frankly, reports of the city’s lack of preparedness for the blazes, Bass’s poor communication in the immediate aftermath, and the mayor’s ongoing feud with former L.A. Fire Department Chief Kristin Crowley. Those concerns aside, the city and county’s current and future leadership in facilitating home and commercial rebuilds — making them move forward as efficiently as possible — is crucial to the entire process.

To her credit, Bass has signed a handful of executive orders aimed at easing L.A.’s notoriously cumbersome building regulations for Palisades residents. They include waiving California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) requirements, directing city departments to expedite permitting in 30 days or less, promoting fire-resistant building materials and civic infrastructure, and suspending the collection of permit and plan-check fees, among others. Yet some experts argue that it hasn’t been nearly enough, given the scale of need.

“There needs to be more common sense and leadership from our cities and our counties, because we’re getting it at the state level, but we need it at the local level too,” said Ellia Thompson, a land use and zoning attorney at law firm Venable. “I think the L.A. City Planning Department is working hard, I think they are definitely trying. I just think some of the officials could be guiding us more than they are.”

Paragon Commercial’s Dillavou was more direct.

“We shouldn’t equivocate about this: I think the leadership has been terrible,” Dillavou said. “I don’t know anyone who lost a house in the fires who is pleased with the leadership in responding to the fires. Not a single person. I think the fact that L.A. has this massive budget deficit isn’t helping. It’s easy for me to say that there’s a big void of leadership, but it’s also a very different issue to figure out how to fund all of these things. Leadership, especially in these municipal situations, often takes money. And there’s just no money available. Maybe everybody is well-meaning, but I think we’re stuck.”

L.A. County, for its part, released in August a rebuilding road map for its unincorporated communities affected by the fires (which includes sections of the Palisades in addition to Altadena). The county’s plan is notable for its clarity of focus and for its emphasis on the financial realities of its residents — another key, long-term challenge in restoring these communities.

“I think the biggest challenges most people face are financial,” Saraiya said. “We’ve heard so many stories from people who have been struggling with insurance companies who are not giving them the full amount of their insurance policies. We’ve had other insurance companies that are unwilling to give them the money on an interim basis to have them pay for their architects and their engineers. … There’s also a component of not wanting to be the first one to rebuild. Kind of waiting to see, ‘OK, are my neighbors coming back? Is my community coming back?’”

Alongside more than $50 million in direct relief funding, the county highlighted plans to keep property taxes for rebuilds low and to increase land value via lot splits and “gentle density,” a concept which gradually increases housing density over time. It also lays out expanded access to lending and bridge funding for home builds, as well as lowers the upfront cost of construction. That can come via waiving energy efficiency requirements and increasing access to affordable contractors.

The county even plans to increase staffing to keep permitting on track, if needed. The city has promised fewer, similar initiatives. It hasn’t released a clear post-cleanup roadmap, either, though a spokesperson for Mayor Bass’s office said that the city is working on a rebuild guide for release “in the coming weeks.” The city earlier this summer selected infrastructure firm AECOM to help develop an infrastructure reconstruction plan for the Palisades, along with a logistics plan for materials management and a master traffic plan, though a timeline for the plans’ release was not immediately clear.

“We had this great kind of inflow of the Army Corps quickly getting debris removed,” Geller said. “But, for us, that’s only phase one of the recovery. I don’t even know if we’re in the bottom of the first inning yet. We find ourselves in this situation where there are a lot of people asking, ‘OK, great, so what’s next?’ And there really isn’t an answer. … Where’s the government, where’s the logistics plan, where’s the buying power? … All of those things that really matter, it feels like we’re not there, and we need the private sector and philanthropy to really help out.”

Both the L.A. Department of Water and Power, for the Palisades, and Southern California Edison (SCE), for Altadena and other parts of the county, have committed to moving some overhead electrical systems underground. SCE is currently facing a class action lawsuit — of which Dillavou’s parents are plaintiffs — for alleged negligence in causing the Eaton fire via faulty power infrastructure.

“Despite facing the worst natural disaster in the city’s history, L.A.’s recovery is on track to be the fastest in state history. … Mayor Bass will continue cutting red tape and streamlining the process to make it faster and safer so that nothing stands in families’ way when they are ready to rebuild,” the mayor’s office told CO in an emailed statement.

Dillavou’s sister, meanwhile, isn’t planning to wait for the city’s assistance. She recently received approval to rebuild her Palisades home — a process that took six months from beginning to end, per Dillavou — and is determined to have the first reconstructed house in her neighborhood, he said, regardless of the empty lots around her.

Yet Dillavou is worried that the energy that powered much of the recovery response earlier this year is petering out, if it hasn’t already. He’s also worried that the expeditious attitude of local authorities is regressing back to its pre-fires level, as the city has more or less returned to normal. Unless local leaders continue to step up, he could be proved right.

“I have a fear that what happens here is the same as what happens after probably most catastrophes across the country, which is that memories are short,” Dillavou said. “Everyone right after the fires, including up until a couple of months ago, was super engaged and focused and helpful. My concern is that that is fading. So I think it’s incumbent on people like me to make sure this stays front of mind.”

Nick Trombola can be reached at ntrombola@commercialobserver.com.