Office Tenants, Owners Gear Up for Congestion Pricing in Manhattan

The tolling system — the first of its kind in the nation — could launch as soon as early next year. Will it be one more speed bump to return to office?

By Mark Hallum June 20, 2023 11:00 am

reprints

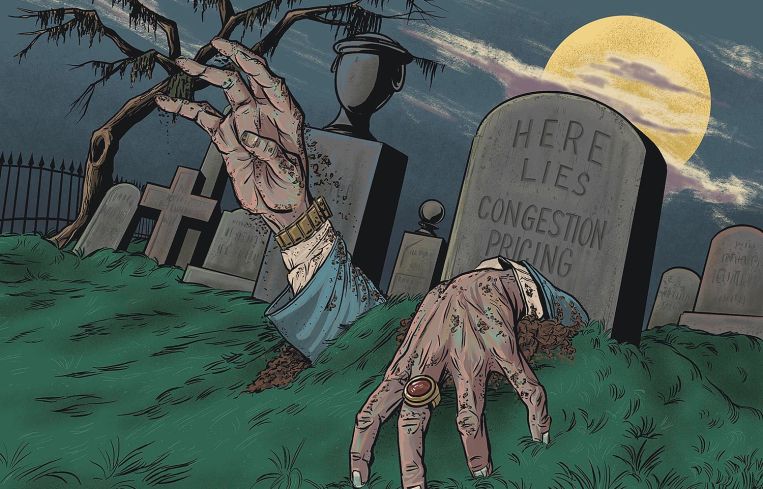

Congestion pricing is a solution for New York City’s economic and environmental woes that can’t (and shouldn’t) die, if you ask some folks in real estate.

June 12 saw the end of the Federal Highway Administration’s (FHWA) 30-day public review period for congestion pricing — a toll proposal that would charge most motorists to drive into central Manhattan during weekdays — but with the office market still languishing in a nadir of low attendance and slow leasing, it begs the question: Does commercial real estate still back the toll?

Let’s say the industry’s in neutral, and willing to shift to drive.

Commercial real estate hasn’t necessarily cooled its support for congestion pricing, an idea that stretches back more than 15 years now, with some sources saying it would only help offices repopulate through reliable transit and improved environmental conditions in the city.

The draft Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI) was completed last week, and the agency is expected to make a final decision by June 27, according to the FHWA’s dashboard. With an 11-month deadline for tolls to be installed, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority expects to be raking in operating funds from motorists by next spring.

Gabe Marans, a vice chairman and tenant broker at Savills, often drives into Manhattan from New Jersey and said he’s willing to eat the cost if it’s for the greater good. Less congestion means more people getting to the office, which equals more deals, Marans told Commercial Observer. Besides it’s a very small number of commuters — only 2 percent of the city’s workforce — who will be forced to pony up on a regular basis, by pre-pandemic estimates.

“It’s not being mentioned as an impediment to a return to office or to the occupancy numbers, because, when you look at the numbers as a percentage of the entire commuting population, the impacted portion is a really small minority,” Marans said. “And I think the concern around some of that population has been the underinvested infrastructure.”

Congestion pricing, formally known as the Central Business District Tolling Program, was introduced by then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo in 2017 during the transit repair-heavy “summer of hell” and approved by the New York State Legislature in 2019. The Trump administration ignored it, but the plan has made significant advances toward approval since President Joe Biden and Department of Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg threw their support behind the idea beginning in 2021. (An earlier congestion pricing plan backed by then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg collapsed in 2008 in the state legislature.)

Meanwhile, the MTA’s coffers have been awaiting an additional $1 billion annually from congestion pricing to fund a $52 billion capital plan. The one-way toll to drive into central Manhattan would be as high as $23, depending on the vehicle.

Not everyone’s comfortable speeding toward congestion pricing at this point. Martin Cottingham, principal of office leasing at Avison Young, believes the market is simply too fragile for any major change of this scale.

His main concerns center around increased traffic into the outer boroughs while giving employees another excuse not to make the trek into Manhattan’s business district. It could also blunt momentum in Manhattan’s subleasing and leasing market as owners and tenants attempt to reposition properties and extract what they can from a dismal climate.

Cottingham said he would rather the MTA continue to focus on things like a crackdown on fare evasion, which could save roughly $500 million annually for the agency.

“We only have limited transportation options,” Cottingham said. “Most of my clients who live in North Jersey drive in, and I just think these additional fees are going to be a real burden on our return to office. During COVID, I remember one of the tenants we spoke to actually shared this with us: A millennial worker in Manhattan, before you even put in eight hours, it’s $50, $60, $70 per day between transportation, lunch and Starbucks. I’m really concerned about this.”

New Jersey motorists opposed to congestion pricing are not without support. U.S. Sen. Bob Menendez of New Jersey introduced federal legislation that, if passed, would cut key federal funding for New York state highway maintenance by 50 percent. The programs that Menendez’s legislation targets would combine to provide up to $1.3 billion to New York state in 2023 alone.

MTA Chairman Janno Lieber — a target of much of the criticism of congestion pricing from opponents, despite taking the helm only in 2021, when the plan was four years old — disregarded the haters in a June 11 interview on WABC-7’s “Up Close With Bill Ritter.” He explained that even though there are downsides, the benefits would be too big to ignore.

“I’m happy to take the flak but the New York State Legislature enacted congestion pricing back in 2019. This is not some crazy idea that Janno Lieber came up with in the middle of the night,” Lieber said. “The bottom line is we have to do something. The business district … is so congested ambulances can’t get to the hospitals, fire trucks can’t get to fires. We’re stopping functions.”

Lieber also doesn’t foresee any surprises in the rollout.

“Congestion pricing has proven in London and Stockholm and a million other places that it works,” Lieber added.

In January, however, City Councilman Joe Borelli of Staten Island called London’s 20-year-old congestion pricing setup an “abject failure” based on a report that showed London still suffers from a lot of traffic jams. Other voices, such as advocacy site Streetsblog, call London’s effort a success.

If there are commercial drivers that will be impacted by the toll, such as cab drivers and other for-hire vehicles, the MTA hopes to have a cap in place so life can go on, with business somewhat as usual. Discounts for lower-income drivers and those traveling overnight through the central business district might also be in the cards.

Anecdotally, much of the pushback on congestion pricing has come from property owners whose businesses rely on the auto industry for their success, said Tiffany-Ann Taylor, vice president for transportation at the Regional Plan Association.

But there will be major perks for retailers.

“I know that there have been more questions about [parking garages], especially for folks who own some of those spaces around the border zones. Like, what do you do with the space if there are fewer vehicles traveling to or near them?” Taylor said. “Remember, goods are traveling on our streets as well. So if there’s less congestion, then trucks should be able to make deliveries faster and more efficiently as well, which is, again, a positive for businesses.”

Parking garages near 60th Street, on the north side of the congestion pricing boundary, will be forced to price their spots very differently, according to Savills’ Marans. Some commuters might want to avoid paying the toll to park their car closer to their workplace. That could affect parking prices by decreasing the number of cars below 60th Street.

“There’s going to be a market-evening from a revenue standpoint — the value of that garage to operators, owners and lenders — but also the prices charged to consumers,” Marans said. “If you can spend less by being two blocks further north, you can bet there’s going to be a movement toward that, and therefore the pricing just north of 60th Street might increase as well. So I suspect that when this rolls out next year, there’s going to be a reshuffling along that northern boundary.”

Some leaders in real estate, whether for or against tolling, are opting for a seat at the table.

In July 2022, the MTA established the Traffic Mobility Review Board to hash out certain details of the proposal and chose a number of industry leaders as board members.

The board is led by Carl Weisbrod, the former director of the New York City Department of City Planning and current senior adviser at HR&A Advisors; Real Estate Board of New York (REBNY) President Emeritus John Banks; RXR CEO Scott Rechler; Velez Organization President Elizabeth Velez; and Kathryn Wylde, the president and CEO of the Partnership for New York City.

Rechler said he could not comment on this story due to his position on the board. But REBNY has come out in favor of the plan.

“Mass transit is New York City’s cardiovascular system and it is critical to the region’s long-term economic health,” REBNY said in a statement on June 12. “Congestion pricing will create a much-needed and sustainable revenue stream for our mass transit infrastructure, while also improving the city’s environment by reducing traffic and air pollution.”

Mark Hallum can be reached at mhallum@commercialobserver.com.