The Boys’ Club: Are Men From Mars and Women from Venus When it Comes to NYC CRE?

By Lauren Elkies Schram January 28, 2015 12:30 pm

reprints

It’s not easy working in New York City real estate, but it’s even more challenging for women, especially on the commercial side.

“I can tell you all the times I say, ‘I’m a real estate developer,’ ” said Abby Hamlin, the president of real estate development company and civic consulting studio Hamlin Ventures. “They say, ‘You sell apartments?’ Then I say, ‘I guess I sell apartments, but first I build them.’ [Laughs] ‘Oh, you mean you’re an architect?’ ‘No, I’m a developer.’”

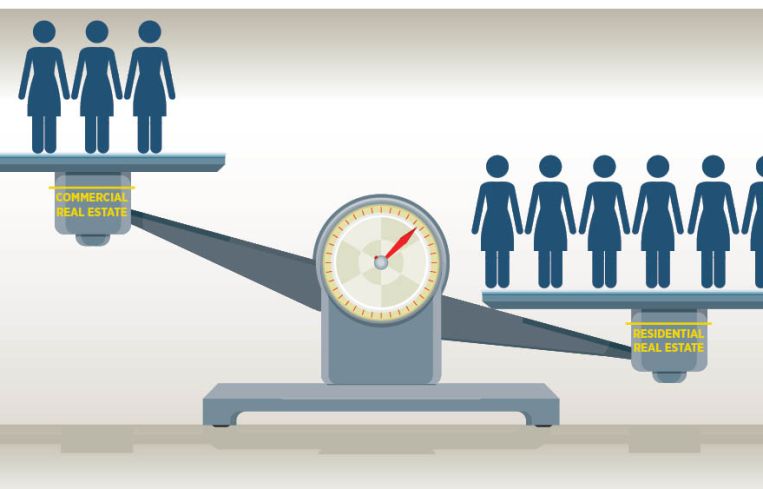

Today, the number of women in the real estate industry in New York City has been on the rise, representing 42 percent of 16,441 Real Estate Board of New York members, according to data provided to Commercial Observer by the New York City industry trade association. That compares with 16 percent of 12,082 REBNY members in 2008, the last year for which data was available. Of the 1,520 commercial brokers today, 32 percent are women versus 18 percent of 1,799 commercial REBNY brokers in 2008. Meanwhile, on the residential side, there is a near 50-50 split between female and male brokers. While REBNY’s membership does not include all of the city’s brokers, it covers the majority.

Why is there such disparity in female representation between commercial and residential brokerage?

The bar of entry to commercial real estate is higher, a number of real estate professionals said. Commercial deals generally occur during traditional business hours rather than in off-hours. The transactions can take a much longer time to conclude (delaying payment of commissions) and there are fewer business opportunities, the latter necessitating good connections. In addition, there are more negotiation points in commercial deals and fewer firms available to bring on new brokers.

None of the real estate professionals Commercial Observer talked with said that it was a matter of choosing between commercial and residential real estate.

Cynthia Foster, who in January left Cushman & Wakefield to join Colliers International as the president of office services, noted that the alternatives to a career in commercial real estate are finance, asset management, development and other areas of banking as opposed to residential real estate.

Residential real estate has traditionally been within the woman’s domain.

“First thing I want to say is that the residential market always has—and this isn’t just true in the city—had a large female workforce because of the opportunities it offered to people who had household obligations—family obligations,” said Mitchell Moss, a professor of urban policy and planning at New York University. The second thing, he said, was that working in the residential market, brokers would need to talk about the characteristics of a home, a topic that women have generally felt comfortable addressing.

Pamela Liebman, the president and chief executive officer of residential real estate giant the Corcoran Group, explained the differences between commercial and residential real estate this way: “Residentially, agents certainly have to be smart and have good business skills, but they need to be able to connect emotionally to their customers and relate to them on a personal level as they make huge decisions in their lives, while commercially it’s less emotional and far more of a financial decision and a business decision. Residential is more emotional. Commercial is more analytical.”

A number of top female brokers, developers and landlords said it was the finance and business aspects that drew them to the commercial real estate business.

Leslie Himmel, of real estate investment company Himmel + Meringoff Properties, repositions, renovates and re-tenants New York City buildings. She went to the University of Pennsylvania for her undergraduate degree followed by Harvard Business School. “I wanted something financially oriented, where I would be involved in financial transactions,” she said.

Daun Paris, the co-founder and president of investment sales brokerage Eastern Consolidated, got started in the business in 1979 and never considered venturing into residential real estate.

“I never even thought of doing anything but commercial,” Ms. Paris said. “In commercial you’re dealing with numbers; you’re dealing with people who are trading. The fact that women didn’t typically do it didn’t matter. I thought it was exciting.”

Perhaps the trailblazer for female commercial brokers was Cecilia Benattar, an English transplant called the “housewife tycoon,” who in the 1960s served as the North American representative of British developer Max Rayne. She was responsible for the demolition of the Savoy Plaza Hotel and the construction of the 50-story, 1.9-million-square-foot General Motors office building in its place in 1968 at 767 Fifth Avenue between East 58th and East 59th Streets and Fifth and Madison Avenues, and the leasing of the building, according to Vicky Ward, author of The Liar’s Ball: The Extraordinary Saga of How One Building Broke the World’s Toughest Tycoons.

“Cecilia was the brains basically behind putting the [GM] building up in the first place,” Ms. Ward said, noting: “Cecilia [who died in 2003] did very well but that’s because she wanted to play in a man’s world.”

At the top of many people’s list of influential women in commercial real estate is Mary Ann Tighe, the chief executive officer of the New York tri-state region of CBRE and the first and only woman appointed chair of REBNY, in 2011.

“Commercial real estate is really basically dealing with corporate entities or companies that are dominated by men,” Ms. Tighe said. “And historically, again going back over time, people hired in their own image—and I mean it quite literally. And so, women didn’t get into it because they probably couldn’t procure the business.

“I also think that there was a strong element of the quantitative, which was off-putting to a lot of women. Really a lot of it had to do with having a strong business background, which women didn’t, whereas the hurdles for entry to residential real estate, again going back over the last several decades, didn’t seem to be so insurmountable for women. Today residential real estate is a lot more complicated—if you’re selling a $25 million-plus apartment you have to know a fair amount about the structuring and the documents, etc.”

Those higher price tags on apartments, like the duplex penthouse at One57 that recently sold for a record $100.5 million, have helped narrow the gap between residential and commercial. The sizable sums give the residential business more “prestige” and “respectability,” Ms. Liebman noted. She added: “With prices being as high as they are, the income levels have drastically increased so it’s more enticing for heads of household to feel real estate would be a great career.”

Faith Hope Consolo, the chairman of Douglas Elliman’s retail leasing and sales division, is celebrating her 30th year in the business. She noted of the retail side: “Even though the women do the shopping, it’s the men that control everything—control the space, control everything.”

While there has been progress in the number of women entering and remaining in commercial real estate and the dollars they rake in, men and women are still not on equal footing.

“The commercial real estate scene … was and still is an industry dominated by men, sometimes with grueling competition and hard, long-working days,” said Sonia K. Bain, a partner at Bryan Cave and co-chair of the mentoring committee at WX, an association of executive-level women in New York commercial real estate industry. “While we have made some significant headway with a few of the largest real estate companies now being run by women it is still somewhat of a ‘boys club’ and can be a very intimidating space for women to try to break into.”

The pivotal role of the developer is particularly dominated by men.

Ms. Hamlin knew her whole life that she wanted to be a developer.

Despite a successful 15-year run thus far with her company, she noted the existence of gender inequality.

“We continue to live within a system with a gender gap,” she said. “The system is broken.”

Women are at a disadvantage, Ms. Hamlin added, because of less access to capital. Also, they are excluded from meetings that occur in venues like golf courses. “It’s not that women need to change who they are,” she added. “I’m proud to say, I succeed in real estate and don’t play golf.”

Helena Rose Durst, a vice president and a fourth-generation family member of the 100-year-old development company Durst Organization, said that commercial real estate is more challenging than residential to break into because it’s “more insular. For a woman, it makes it more difficult to break that glass ceiling, as it were.”

When Maryanne Gilmartin, the CEO and president of development company Forest City Ratner Companies, entered the business 29 years ago, “it was a cowboy career, fueled by testosterone and defined by bravado and ego.” She further noted that in the development world, it was dynasty driven. In addition, there were few role models.

She said it was serendipitous that she entered the business.

“I won an urban fellowship and started in economic development under [Mayor Ed] Koch,” Ms. Gilmartin said, “and got real estate in my veins from that.”

She added that as a developer it was “disheartening” that there were few women running real estate companies in the 1980s and that that is still the case today.

“I will say women have arrived in this sector of real estate when we talk about real estate, not just women in real estate,” Ms. Gilmartin said.

With additional reporting provided by Max Gross.