Of Price and Performance: Just How Much Instability Is There in Asset Pricing?

By Sam Chandan August 26, 2010 2:28 pm

reprints The Moody’s/REAL Commercial Property Price Index (CPPI) fell by 4 percent in June, marking the first decline in same-property sales prices since March and one of the sharpest one-month percentage drops since the CPPI’s inception. Ceding gains from April and May, the index has fallen by just over 0.9 percent during the first half of 2010, from an index value of 113.6 in December 2009 to 112.5 in June.

The Moody’s/REAL Commercial Property Price Index (CPPI) fell by 4 percent in June, marking the first decline in same-property sales prices since March and one of the sharpest one-month percentage drops since the CPPI’s inception. Ceding gains from April and May, the index has fallen by just over 0.9 percent during the first half of 2010, from an index value of 113.6 in December 2009 to 112.5 in June.

While 4.2 percent above its recent low point last October, the index remains 41.4 percent below its October 2007 peak.

More Than Meets the Eye

The June decline in the all-property index is the fifth largest percentage drop in the 115-month index history and the largest since July 2009.

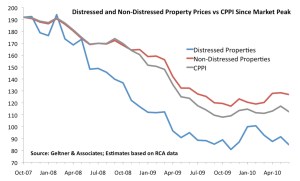

In spite of the relatively large decline, we should be cautious when interpreting the result as evidence of renewed instability in the pricing trends for performing assets. Essential to the assessment of the current index trend, including the June measurement, the share of transactions related to distress has been increasing steadily over the past 18 months. In turn, this larger share of distress sales has exerted greater downward pressure on the aggregate measure of same-property prices.

The headline price trend captured in the all-property index masks the underlying variation in the price performance of distressed and non-distressed properties, obscuring the latter’s more stable trajectory.

In June, in particular, the impact of distress sales on the aggregate index dominated the more stable result for voluntary, non-distress transactions of commercial properties. Distress sales accounted for approximately 28 percent of same-property pairs in the June index calculation, generally consistent with recent trends and markedly higher than during 2008 and 2009.

Word of the Day: Endogenous

In economic terms, distress and pricing are endogenous in property performance. The price of a sale out of distress may be lower than for properties unencumbered by debt-related distress because the former are of lower quality or deteriorate in quality, or because of low or declining contributors to cash flow, including occupancy and rent levels. In the case where the asset is real estate owned (REO) by the lender, cash and non-cash holding costs-including regulatory scrutiny-may compel sales at lower prices.

In either case, borrowers on the cusp of default and lenders holding assets respond to incentives that result in properties being sold at relative discounts; and so we observe a relatively healthier index trend for non-distress transactions where private buyers and sellers voluntarily engage in mutually beneficial trades.

The contribution of distress to the index trend is hardly an issue that is unique to the commercial property sector. First and foremost, there is the basic question of the direct impact of generally lower-priced distress sales on the aggregate index result. Bifurcation of repeat sales so as to show the index with and without distress transactions is a simple way to illustrate the magnitude of the difference in the separate index vectors. But apart from the separation of the pooled observations, we must also consider the indirect impact of distress sales on the market, inasmuch as distress sales might impact prices for performing assets.

Intuitively, it stands to reason that geographically proximate distress sales of hedonically comparable properties will undermine pricing for the non-distress assets.

But whether this hypothetical and anecdotal relationship can be demonstrated empirically is an open question. Thus far, there has been a paucity of formal inquiry into the question of externalities related to distress in commercial property prices. The question is clearly important; the absence of research reflects, in part, that reliable micro data sets from periods of systemic distress in commercial real estate debt markets have not been available until the current downturn.

Rising Distress Sales Reflect Complex Incentive Structures

Apart from the absence of formal research into the presence and extent of contagion effects resulting from distress commercial real estate sales, the current policy environment complicates the hypothesized relationship between distress sales activity and the pricing of non-distress sales.

Over the past year, significant adjustments in regulatory guidance have altered the incentives for lenders to sell REO as opposed to holding assets. Specifically, the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) released its Policy Statement on Prudent Commercial Real Estate Loan Workouts in late October 2009. A month earlier, the I.R.S. and Treasury had also clarified certain rules bearing on the modification securitized commercial mortgages.

In part, the regulatory guidance reflects that thinly traded property markets limit price discovery and that prices have fallen so significantly. For the bank holding assets, the sale of REO at this point might imply very large losses. The new flexibility means that a bank lender is more likely to respond to incentives for loss mitigation: If the expected value of the distress sale implies a larger loss than a modification of the loan, the lender should be able to opt for the latter alternative.

In this calculus, the probability that a lender will pursue a distress sale is increasing in transaction activity and price metrics. We should observe a rise in distress sales because pricing is firming. Independent of the price vector’s direction, rising transaction activity enhances price discovery and should narrow the ex post spread around the expected value. This is important if the lender is risk-averse in its decision-making.

With these relationships in mind, the increase in transaction activity related to distress may reflect the impact of an increase in price stability of non-distress property sales and a resulting response in lender behavior. All of this notwithstanding downward adjustments to the economic outlook and updates to related projections for property fundamentals.

If this is the case, then the rise in distress sales actually reflects that the market’s underlying price trend and capacity to absorb additional supply at higher market clearing prices is improving—even if the increase in the distress share itself is depressing the headline price index.

schandan@rcanalytics.com

Sam Chandan, Ph.D., is global chief economist and executive vice president of Real Capital Analytics and an adjunct professor of real estate at Wharton.