The Plan: A Look at ESRT’s 76-Foot Video Ceiling at 250 West 57th Street

By Liam La Guerre November 7, 2017 6:01 pm

reprints

When Anthony Malkin, the chairman and chief executive officer of Empire State Realty Trust, set out to renovate the 537,839-square-foot office building at 250 West 57th Street last year, he wanted a lobby on its own to attract higher paying tenants.

“I did not want to do another white lobby, I didn’t want to do another black lobby,” Malkin told Commercial Observer. “I didn’t want plants or a water feature. We wanted to do something that had never been done. And we didn’t want to have one big piece of art. We wanted something special, unique—something that is alive.”

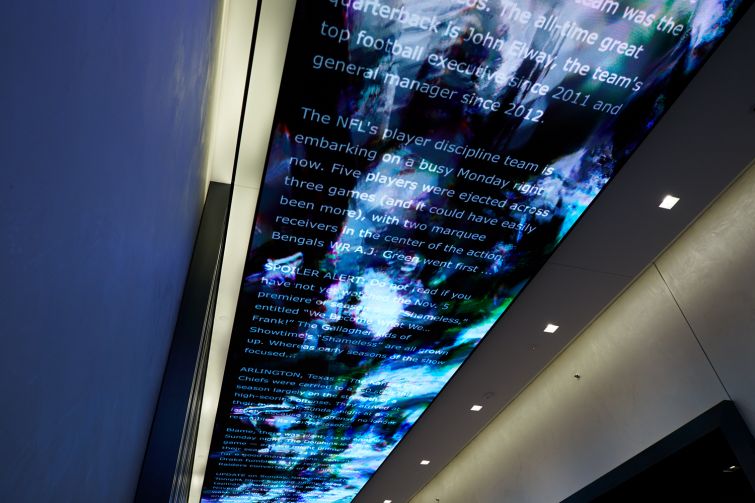

What his company came up with is a large screen that spans the majority of the ceiling in the lobby and shows a vibrant array of colors and images. The 75.7-foot-long and 7.8-foot-wide LED screen, created by VER, alone cost $2.5 million of the $21 million building renovation. It will be officially revealed at an event this week. The high definition screen displays 6.7 million pixels and functions with two processors.

Marc Brickman of Tactical Manoeuvre, the man responsible for the lighting displays at the top of the Empire State Building as well as lighting designs for Hans Zimmer and Pink Floyd performances, was hired to bring the screen alive. Brickman’s company used various algorithms and coding to operate the screen and allow it to show content thought up by artist Lindsay Scoggins, whose video art has millions of views on YouTube and has been displayed in the Guggenheim Museum. Brickman calls the final product “fine digital art.”

Every morning, the screen will start showing a sunrise across its length for two hours and weather in real time, then it moves into a variety of other timed segments. The next is news, which is scraped from news websites and flows on the screen with an abstract background. This section is followed by one called “morphing the present,” in which pictures of people—celebrities and public figures—are blended and blurred, providing glimpses of those individuals.

Next is “sea of cities,” which looks like stain-glass windows where the images (taken from scenes in the five boroughs pulled from social media) move up and down, a little like the waves of an ocean. (Individually, the images are abstracted and made unrecognizable.) This is followed by a sunset with a variety of colors—think, Aurora Borealis. All of the 1s and 0s coding for the images is posted in the next segment called “source code.” And, finally, there is “a questionable time,” which features black holes and planets at the end of the day.

“Other buildings have video installations, and they repeat themselves constantly,” Brickman said. “What I wanted to do was have [tenants] feel like this greets them every day, and they have the choice of interacting with it, in terms of finding out what it is about. That was the motivation of creating it this way, rather than just putting up pictures from the internet or flowers. We are trying to up the game.”

Besides the screen, the 26-story building’s renovation included a revitalized lobby with black granite floors and metal fixtures designed by Gensler, a new building canopy and new black granite storefronts to replace the “hodgepodge” of precast concrete and limestone. Next phase is to modernize the building’s 10 elevator cabs, which will be completed by the end of 2018, Malkin said.

The screen, which will become the center of attention for the building, is 20 feet off the entrance, so passersby won’t see it. And it won’t be used for advertisements (and will not generate further revenue for the building).

“The significance of this ceiling is not to draw people inside—it’s specially for our tenants,” Malkin said. “[And] specially for their visitors. It’s not a museum. But it’s of museum quality.”