Bushwick’s Warehouse Conversions Are Hitting Never-Before-Seen Heights

By Liam La Guerre February 10, 2016 9:00 am

reprints

Two years ago there were four sales of industrial property in Bushwick, Brooklyn, totaling a modest $8.4 million, according to TerraCRG’s 2014 annual end-of-year market report.

Last year’s numbers were a wee bit better: $115.7 million.

It might be eye-popping. Or it might be part of the inevitable progression of a neighborhood, which has had so many factors in its favor, from its proximity to Williamsburg, to a coveted L train wending its way to Manhattan, to cheaper rents, which have never been so sought after. (The other amazing thing about TerraCRG’s $115.7 million figure is it represents only eight sales. So, yes, while activity has increased, prices have shot up even more dramatically.)

Ever since Chris Parachini, Brandon Hoy and Carlo Mirarchi planted their flag on a gritty, industrial corner of Moore and Bogart Streets in 2008 and opened Roberta’s, Bushwick’s industrial building stock has had a second life as bars, theaters, music venues, specialty gyms and just about anything boutique or hipster-approved. And this intrigue has extended to developers, who are now purchasing and transforming former industrial Bushwick buildings in yet another, bigger wave of conversion.

“When it comes to conversions those are primarily driven by the fact that those buildings are being offered significantly under the replacement costs,” said Jakub Nowak, an associate broker at Marcus & Millichap’s Brooklyn office. “You’re getting a bargain compared to what it would cost to build a building like that ground up.”

And this is much needed for locals. “In Bushwick, there are very few amenities,” said Barry Fishbach, a vice president at RKF. The drugstores and restaurants popping up are already “improving the quality of life.”

Bushwack Capital, a five-year-old company headed by Dawson Stellberger and Jon Killkelley, is one of the companies that has been buying and converting properties in Bushwick. (As for the company name, it is not just a play on “Bushwick”—apparently Mr. Killkelley really does have an actual fondness for clearing trails in the wilderness.)

The landlord is winding down the conversion of a 22,000-square-foot building at 99 Scott Avenue, and the duo is speaking to a tenant who will turn the space in to an event hall that could accommodate concerts in one part of the property. Plus, Messrs. Killkelly and Stellberger plan on putting a bar and restaurant as well as a winery on the ground floor and office space on the second floor.

Bushwack has already leased a portion of the second-floor office space to ABS Partners Real Estate; Farmigo, a food distributor, took space on the ground floor. The asking rent for the retail space was $30 per square foot—a fairly typical figure for rents in the area—which is another major reason why retailers have been gobbling up Bushwick space as well: Ground-floor retail prices start at $30 per square foot and go up to $50 per square foot in prime buildings near subway stations.

“Being in an area that’s up and coming and that’s very accessible to [Manhattan], I think 30 bucks is a very reasonable rent,” said Mr. Stellberger. “In Williamsburg they are asking $100 or $200 a foot.”

At 58 Grattan Street, the firm has filed for a variance from the New York City Board of Standards and Appeals to build a 6,000-square-foot, three-story building on the vacant site with the goal of starting construction this year. Mr. Stellberger said he and his partner hope to erect a building for light industrial and retail tenants. And at 599 Johnson Avenue the developers will expand the structure to 21,815 square feet from 13,866 square feet for a music venue and retail tenants.

Bushwick is “a blank canvas to some extent,” Mr. Stellberger said. “There are a lot of cool buildings and a lot of things that you could do with them.”

Even more established companies are diving into the area for the chance to get in before it becomes too hot (like Williamsburg did).

Normandy Real Estate Partners, Royalton Capital and Sciame Development purchased 333 Johnson Avenue between White and Bogart Streets for about $27 million last May. The 160,000-square-foot industrial building, which once housed a printing company, will be converted into offices and retail, and there will be 40,000 square feet for outdoor common space, according to Brownstoner.

Developers Toby Moskovits’ Heritage Equity Partners and Lichtenstein Group are working on an office building called The Bushwick Generator at 215 Moore Street, which was the site of a steel fabricator. On the border of East Williamsburg, the 75,000-square-foot building will also include some light industrial tenants and space for retailers.

The project is expected to be completed later this year and has already signed its first tenant CartoBD, a startup that offers mapping and data analysis tools, to a four-year, 7,500-square-foot lease. The asking rents are $50 per square foot, as Commercial Observer previously reported.

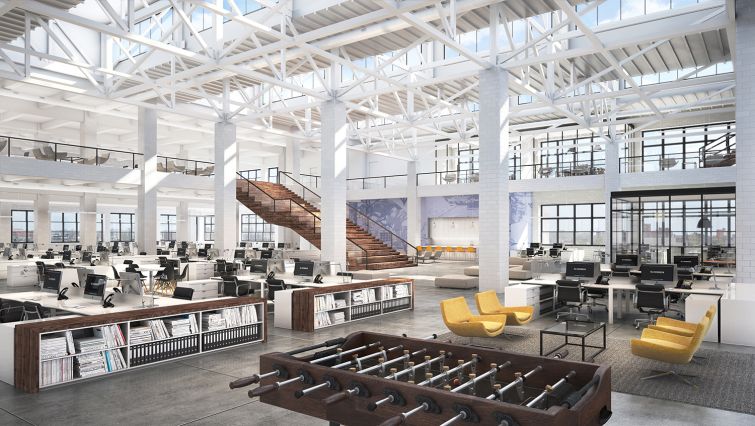

And Savanna and Hornig Capital Partners are spending $30 million to convert the former five-story Schlitz Brewery at 95 Evergreen Avenue into a Class-A office building. The partnership purchased the 170,000-square-foot property last year for $33.7 million, as CO reported at that time. The building will be able to accommodate larger companies with 37,000-square-foot floor plates.

The project is expected to be completed in June. The office and retail spaces have asking rents in the $40s and $50s per square foot, said Tom Farrell, a managing director at Savanna. There has been a lot of interest from companies in Manhattan for space in the building.

“The two main groups are folks in Midtown South or the Financial District, and they have expiring leases but a lot of employees in Brooklyn,” Mr. Farrell said.

In the retail portion of the project, on the lower floors, the landlords are hoping to have local restaurants and art galleries; the upper floors will be for office tenants.

One can see these sorts of plans unfolding with some of the tenants who have recently set up shop: Kevin Adey, who has lived in the neighborhood for the past seven years, opened the Italian restaurant Faro in a former storage warehouse at 436 Jefferson Street last May with his wife Debbie. His 30 employees are all Bushwick residents as well. His eatery is fully in tune with the fresh, organic, locally made philosophy that gives Bushwick its hipster credentials. Mr. Adey mills hundreds of pounds of flour each week to serve 1,500 orders of pasta and more than 30 loaves of bread each day in the 2,500-square-foot, 60-seat restaurant.

“There are people here who eat out quite a bit from all walks of life, and I thought that I could provide for them,” Mr. Adey said.

Williamsburg-based Third Rail Projects, an experiential dance theater company, created The Grand Paradise from a one-story, 5,000-square-foot warehouse at 383 Troutman Street in December 2015. The show, which includes a scene with a human-sized aquarium, has an immersive experience with the audience.

And Syndicated, a bar, restaurant and movie theater mix, opened just a few weeks ago at 40 Bogart Street.

“There isn’t anything like this in the neighborhood,” said Tim Chung, a Williamsburg resident and managing partner of Syndicated. “There wasn’t a movie theater prior to us. I think we are filling a gap.”

All of the conversions are possible because many of the area’s manufacturing-zoned properties can be converted for commercial and retail uses. Seeing the increased demand, many generational owners of those structures saw the opportunity to cash out or allow tenants to change the buildings.

“By and large, many of the commercial areas of Brooklyn where there are these industrial warehouses have been converted to residential,” Mr. Farrell said. “Unlike Downtown Brooklyn, Dumbo and Williamsburg, Bushwick still has a distinct separation between the commercial area and the residential area.”

And Bushwick’s established residential community had long shrugged off national retailers and chains.

“You are not getting a lot of credit tenants and national chains. It’s a lot of local people that live and work around there that want to support their neighbors,” said Dan Marks, a senior vice president at TerraCRG.

“I think the national guys will come, just as they did in Williamsburg,” Mr. Farrell said. “I think it’s just a matter of time before they are pushing into Bushwick.”