Behind the Juice Craze Pressing Through the City

By Al Barbarino January 28, 2014 12:00 pm

reprints

During one of his infamous Power Juicer infomercials from the early 1990s, a stunningly fit-for-his-age Jack LaLanne declared, “That’s the power of the juice!”

Mr. LaLanne, known as the Godfather of Fitness, lived to be 96 and swore that juicing had transformed him from an ill and frail teenager into the fitness extremist who, well into his golden years, took a liking to towing boats while swimming shackled and handcuffed.

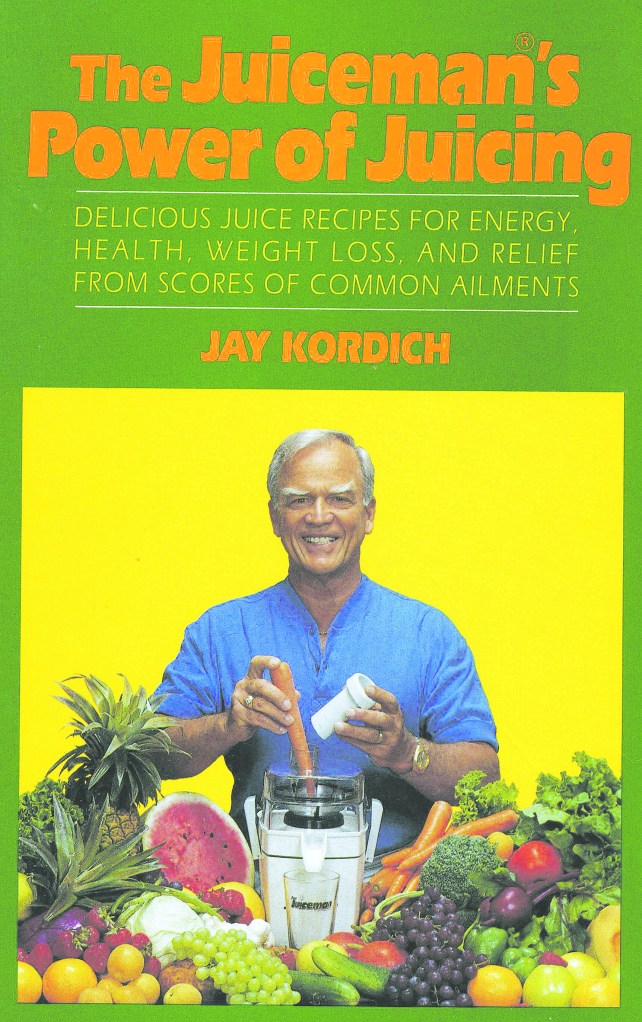

Public skepticism regarding juicing at the time was perhaps best personified by actor and comedian Jim Carrey, then a cast member of the cult classic TV sketch comedy series In Living Color, who in a spoof of Mr. LaLanne’s infomercial rival, “Father of Juicing” Jay Kordich, showed up at the set of a mock infomercial towing an R.V. with his teeth.

Juicing proponents continue to tout the benefits of juice and so-called “juice cleanse” diets, though the claims are not backed by science. But the concept of fresh juice as a healthy choice is arguably more accepted today than it was in previous decades, with retailers successfully playing off that notion and transforming a longtime staple of the American diet into a premium commodity not unlike a cup of Starbuck’s coffee.

“The retail consumer is ripe and ready for this health movement to be a part of their lives,” said Marcus Antebi, the chief executive of Juice Press, which is among the fastest growing retailers in the fresh juice category. “People have become competitive about their health. People want to be healthy.”

Retail professionals like Mr. Antebi set out with expansion plans that were prebuilt into their business models. Juice Press, funded and partnered by a group of investors that includes New York Yankees first baseman Mark Teixeira, will soon have 20 stores throughout the New York City area after first setting up shop just a few years ago at 70 East First Street.

“There’s no one out there who’s expanding as fast as I am,” said Mr. Antebi, a self-proclaimed “assassin” in the juice space. “But I really still think we’re in the infancy stages here. We just discovered the light bulb. If we stop at 20 stores, then we aren’t successful.”

But the top names in the fresh juice store category are expanding too, and when coupled with the independent stores squeezing juice from the corners of delis and supermarkets, the concoctions of fruits and veggies once reserved for the raw-food fitness freaks, the closet Jack LaLannes and Jay Kordich wannabes are now an option on almost every New York City corner.

Juice Generation, which already has more than 10 locations throughout Manhattan, recently made its foray into Williamsburg, Brooklyn, with a deal at 210 Bedford Avenue. It took “cold-pressed” juice pioneer Liquiteria 17 years to expand from the shop it opened in 1996 on Second Avenue in the East Village to its second store, which opened in Chelsea last September, the result of an ownership change and investor confidence in the brand.

“When you have 17 years between two stores, you’re not really sure what’s going to happen, but fortunately, the new store was literally just as full as the first location the day we opened,” said Christine Graves, chief marketing officer at Liquiteria.

Investors are now throwing the kind of cash once reserved for tech start-ups in the direction of juice stores, who are reaping celebrity endorsements and gym deals as they expand.

Mr. Antebi not only sold stakes of Juice Press to Kenny Dichter, who founded the aviation company Marquis Jet, and Mr. Teixeira but also raised an additional $7 million in venture capital from investors, including hedge fund manager Stan Druckenmiller and Home Depot’s Ken Langone.

Weld North CEO Jonathan Grayer now owns a majority stake in Organic Avenue, which has nine locations in New York City and is expanding. And the restaurateur Danny Meyer (Union Square Café, Shake Shack) developed Creative Juice, to be sold at Equinox gyms.

Liquiteria’s expansion was spawned after founder Doug Green sold the company to a private group of investors who plan to expand the retailer into three additional locations by June 2014, including a Greenwich Village location in the former Gray’s Papaya.

“Really, another juice bar?” wrote one commenter on the popular food site Eater.com, reacting to the news.

It seems indicative of a cultural shift that a juice store will move into the famous Gray’s Papaya location, where the perennial hot ticket item was the “recession special,” consisting of two hot dogs and a medium drink for $4.95. Liquiteria’s cold-pressed juices, which at $7 tend to fall at the lower end of the juice store pricing spectrum, might include some combination of apple, lemon, ginger, kale, spinach, romaine, parsley, celery and cucumber.

Ms. Graves stated simply that “the space was vacant and we took it,” noting that Liquiteria employees were fans of Gray’s Papaya and adding that “we wish that they wouldn’t have gone out of business.”

But Ms. Graves, Mr. Antebi and others in the business aren’t shying away from making some of the same arguments regarding the healing power of juice and the so-called “juice cleanse” that the infomercial juice-men were making well before it was cool: It increases energy, acts as an anti-inflammatory, reduces toxicity and clears the mind and the skin, to name just a few.

“Juice is food in a liquid format, minus all the toxic material,” said Mr. Antebi, who claimed he helped “tens of thousands of people” with juice fasts that yielded “miraculous” results. “I can live on juice indefinitely, because it has pretty much all the nutrition that I need to allow myself to do the things I want to do.”

Cold-pressed juice, typically sold in 16 ounce bottles with a shelf life of no longer than three days, is made by literally pressing fruits and veggies under high pressure until juice trickles out. It is a more time-consuming, labor-intensive process and uses far more fruits and vegetables than the conventional blade-driven method that is used if you order a juice and have it squeezed before your eyes.

“Some of our bottles of juice have anywhere between 3 and 6 pounds of [juiced] produce in the bottle, which, along with the labor, drives costs,” said Ms. Graves, who generally recommends a juice cleanse lasting between one and three days. “The miracle of cold-pressed juice is that there’s no heat applied, so it retains all of the enzymes, minerals and vitamins intended, and that makes a very big difference in the way people feel when they consume it.”

It seems logical that our seemingly gym-, Pilates- and zumba-obsessed, yoga-preaching, CrossFit-crazed city is more likely to seek a natural boost. Some might even attribute it to the decline—not to mention the staunch denunciation from former Mayor Michael Bloomberg—of soda and other sugary drinks.

But, in fact, consumption of soda and juice has actually declined across the country at roughly the same rate over the past decade, according to statistics from the consumer market researchers at NPD Group, which outlined the top 10 foods and beverages consumed by Americans (in the home and away from home).

Soda dropped in popularity from the No. 2 spot in 2003 to the No. 4 spot in 2013, while fruit juice dropped from No. 7 to No. 9 (sandwiches took the top spot both years).

“It’s not that these things are being consumed more; it’s about finding new concepts for things that are already important for the American diet,” said Harry Balzer, a chief industry analyst at NPD Group and an expert on food and diet trends. “You wouldn’t be talking about anybody who was making rice cakes.”

“The whole food service industry has been all about making life easier,” he said. “If you can demonstrate either that you can make my life easier or that you make my food cheaper, then you’re going to be around for a long time.”

It’s not about health either, Mr. Balzer insisted, noting the explosion of gyms that occurred in the ’70s and ’80s.

“We always wanted to be healthy,” he said. “No one wants to be sicker.”

What’s more is that the health claims made by the pro-juice movement are difficult, if not impossible, to back up. The American Cancer Society states that there is “no convincing scientific evidence that extracted juices are healthier than whole foods.”

Organs like the kidneys and liver are already devoted to cleansing, and the gastrointestinal system is made to break down solid food in order to obtain essential nutrients and insoluble fibers, noted Rebecca Appleman, a registered dietician and founder of Appleman Nutrition in New York City.

“Fruit juicing has the potential for very obvious inadequacies in protein, fat and fiber—vital meal components that are critical for metabolic efficiency, as well as satiety,” she said in an email. “For those who are overeating or eating poorly, ‘juicing’ for a few days might feel like a boost to a better you, but it isn’t long-lasting.”

“Enjoying a glass of calcium-fortified O.J. or a glass of antioxidant-rich pomegranate-blueberry juice with breakfast a few times per week is a far superior way to benefit from juice’s health bonuses than subjecting the body to a juice ‘cleanse’ over a period of days,” she added.

Not surprisingly, Mr. Antebi disagreed.

“If you asked me to do a 500-day juice fast on my own, I could do it, and I’d do fine. In fact, I’d be fabulous,” he said. “I’d be extremely skinny, and I probably wouldn’t want to talk to people anymore, because everybody is so toxic, including me. When you get that clean, it’s actually mind-numbing how you have a very low tolerance for the things that people do.”

Finally, Mr. Antebi reflected on the life of Jack LaLanne.

“The man was a genius,” he said. “He would have lived longer, but from what I heard from someone who knew him, he started making a lot of mistakes in his diet.”