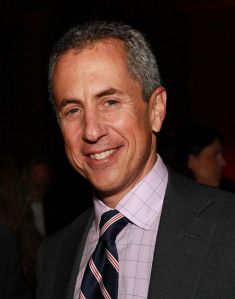

As arguably the most influential New York restaurateur of the past 30 years, Danny Meyer has altered Manhattan’s culinary map and helped redraw its real estate borders. Starting with Union Square Café in 1985, growing exponentially with Shake Shack and moving forward with NoMad, Brooklyn and JFK airport concepts, Mr. Meyer’s Union Square Hospitality Group presaged the Midtown South gold rush and nurtured a generation of top toques while redefining restaurant hospitality. Mr. Meyer spoke to The Commercial Observer about the gentrification his restaurants are credited with jumpstarting, the decriminalization of mall dining in New York and the city’s untapped restaurant rows. This interview was conducted prior to his ICSC New York keynote address Monday.

You’re kicking off this year’s ICSC New York conference with a speech to the general session. What do you have planned?

I’m not really sure [laughs]. Without being glib about it, I’m incapable of reading a speech. To the degree that I can make a public presentation, it’s because I’m as literate at reading a crowd as I am illiterate at reading a speech. But I’m incredibly excited about it.

To be a bit more specific, the goal is to try to present a perspective from a restaurateur on why restaurants would or would not want to position themselves within the kind of properties that this audience represents. It’s a different generation. If you look at shopping centers as if they were magazines, the editorial content is the various opportunities to shop there. What you want in a newspaper or magazine is enough really good articles that will keep you coming back to the publication even if you might not be fascinated by every single article.

With the Internet now, people still use shopping centers as a way to be with people. But they don’t have to spend money there. And it’s now clear to this sector that the food experience now may be the primary reason people come, as opposed to the old guard where you had to have some restaurants as an amenity to keep people shopping. As smart as my phone is, it still can’t cook food and do the dishes for me.

There are fewer full-fledged shopping malls in New York than other cities. But between the Time Warner Center and the upcoming Brookfield Place’s food vendors, do you think the stigma of eating in a mall has faded?

Yes. The Time Warner Center really broke the mold for Manhattan. I was completely close-minded to that when it came about. The notion that there are two four-star New York Times restaurants within that center has certainly proven to New Yorkers that whatever stigma we may have applied to it is no longer there. Also, internationally, especially in the Far East, it’s almost impossible to find a good restaurant that’s ground level.

What about the changes around Union Square, where you got your start and which is now teeming with chains? Do you think a restaurant like Union Square Café helped make the neighborhood a victim of its own success?

Well, I think there will always be parts of Manhattan where independent business owners can still open and thrive. I remember when you could walk into any storefront in the Meatpacking District and people looked at you like you were crazy. Then if it works over time, it tends to get overheated, and the only people who can afford the rents tend to be national chains. That prices out the innovators.

Has that happened in Union Square over time? Yes. But there are still pockets within Union Square where entrepreneurs can open up. For example, Dos Toros is a block off Union Square. And 17th Street between Broadway and Fifth Avenue is not inexpensive, but there are still opportunities for entrepreneurs to open there. City Bakery opened there before it got big. And [grass-fed hot dog joint] Dogmatic recently opened there. [Note: Dogmatic closed its 17th Street store in June and is relocating to MacDougal Street in June.]

But it is true that our business strategy—or, before it was strategy, intuition—has always been to find neighborhoods or pockets within neighborhoods that seemed to have their best days ahead of them, lock in a very fair rent and help grow to where we’re spending our revenues on managerial talent rather than putting it into the pockets of the landlords. This worked with Union Square and Gramercy, and we’re hoping it works down in Battery Park City. The Brookfield example is a good illustration.

USHG recently announced an upcoming restaurant in the King & Grove hotel at 29 East 29th Street. Do you think NoMad is still one of those pockets with potential?

Oh, I know it is. Actually, I should say that we’re confident there’s this rich stock of small boutique beaux arts hotels that are roughly 100 years old and have gone through all kinds of cycles including glory days and down-and-out days as SRO units. They’re coming back.

And does the King & Grove spot have a name?

I think it’s still unnamed, but we’re narrowing it down.

As of a few years ago, USHG opened a new restaurant every four years or so. Why the speedup?

It’s generational. And it’s basically recognizing that we have a number of really talented people on our team who are in their 30s or early 40s right now who’ve been with us for close to 20 years. They want to grow, and they want to stay with the family. We give those people who are entrepreneurial an opportunity to do that. And we didn’t have that opportunity 10 years ago.

Another new USHG project is a café at Theatre for a New Audience’s new permanent home in Fort Greene. How has the run-up to that gone?

One detail I can offer is that the story was sort of misreported. It seemed to come out that it would be a café. The fact is that it’s what we hope will be a wonderful concession for the theater. I think the plan is for people attending the theater. It’s tiny and not full-service and open only when the theater is showing plays.

How would you compare today’s Brooklyn restaurant scene to downtown Manhattan’s 30 years ago?

I think it’s different. Brooklyn is geographically so much bigger than Manhattan, while a lot of spaces are smaller-scale. Because of the sprawl and the small spaces, the runway is a lot longer for innovative entrepreneurs to open spaces on a much smaller budget. I know in pockets like Williamsburg the rents are going up like crazy. But that’s when you get a Bushwick or Bed-Stuy. But the thing about Union Square is it’s getting so old that it’s going to be new again.

On to Queens and beyond, what drew you to opening a Shake Shack and Blue Smoke at JFK’s Terminal 4?

I think Shake Shack has been the one part of our business that we’ve really learned to grow. And we’re working on it with Blue Smoke, which is already in two ballparks. And an airport is not a big stretch from that.

Is there any truth to the rumors about USHG restaurants opening on Pier 26 and in Harlem?

No. The Harlem one has been persistent to the point that people don’t believe me when I say “no.” A broker actually spread a rumor, which is a great way to never do business with someone. And I don’t even know where Pier 26 is.