REBNY Officers Look Back And Ahead, Bet On Mayor’s Race, Midtown East Rezoning

By Billy Gray January 15, 2013 7:00 am

reprintsThe new year ushered in a shaken-up hierarchy to the Real Estate Board of New York.

Tishman Speyer President Rob Speyer has replaced Mary Ann Tighe as chairman. Mr. Speyer, 43, is the youngest chairman in the board’s 117-year history, and will inherit the position from the first female to ever hold it. Despite his youth, Mr. Speyer has history on his side: he’s the third generation of his family to be named REBNY chair.

Mr. Speyer’s combination of youth and lineage is well-suited to an organization that in 2012 faced fresh, modern challenges whose resolutions required the full weight of the influence REBNY has accrued over the past century. Hurricane Sandy caused unprecedented damage to coastal areas of the city and its transportation system, not to mention the related electric grid failure. And while major storms are nothing new, they seem on course to increase in size and frequency. After Sandy, REBNY lobbied politicians for desperately needed federal relief aid, housing recovery plans and disaster preparedness measures; formed and deployed ad hoc task forces to hard-hit communities; and worked to restore service to damaged commercial buildings as it temporarily relocated displaced firms and their employees from lower Manhattan to Midtown and other neighborhoods largely spared by the storm.

After Sandy, REBNY lobbied politicians for desperately needed federal relief aid, housing recovery plans and disaster preparedness measures; formed and deployed ad hoc task forces to hard-hit communities; and worked to restore service to damaged commercial buildings as it temporarily relocated displaced firms and their employees from lower Manhattan to Midtown and other neighborhoods largely spared by the storm.

“I think the board’s response to Sandy was excellent,” Steve Siegel, the chairman of global brokerage at CBRE (CBRE), said. “Bottom line, they did everything within their power beyond writing a multibillion-dollar check.”

While REBNY helped the city cope with its devastation after Sandy, the board also opposed efforts to preserve what some New Yorkers consider profound losses of local character. REBNY fought against proposed historic districts and commercial zoning restrictions in the Upper West Side, Lower East Side and Downtown Brooklyn, suggesting that while the board might care about striking a balance between preservation and development, it finds the most prominent existing methods of doing that inefficient.

“Preserving certain neighborhoods is great,” Robert Knakal, a REBNY officer and the chairman and founding partner of Massey Knakal Realty Services, said. “But once you start regulating how big stores and storefronts can be—that’s dangerous. If the whole city becomes a historic district, New York will no longer be the capital of the world.” Mr. Siegel echoed that sentiment, calling downzoning a very serious problem and saying, “there should be parameters for growth, but to do nothing is an absolute error in judgment.”

The real estate industry’s perennial tussle with preservationists grew to a fever pitch with the Midtown East rezoning proposal, a centerpiece legislative issue introduced last fall that will be near the forefront of REBNY’s agenda for years to come. The Municipal Art Society and other urban planning organizations questioned the wisdom of a plan that seeks to increase the maximum allowable building density by 60 percent in New York’s pre-eminent business district, and fretted over its impact on notable buildings that lack landmark status.

REBNY countered by saying that the neighborhood’s building stock, especially in the area surrounding Grand Central Terminal, is woefully outdated—the average building in the 78-block designated zone is just over 70 years old, according to figures from the Department of City Planning’s East Midtown Study—and at risk of losing its global cachet as comparable office districts in cities like London and Hong Kong race to the future.

Steven Spinola, the president of REBNY, dismissed many concerns as manufactured hand-wringing.

“I will not apologize to anyone about my industry’s concern for maintenance of landmark buildings that are truly landmark-worthy,” Mr. Spinola said. “It’s amazing that all of a sudden, once rezoning is proposed, these groups are calling for another 30-odd buildings to be landmarked. You tell me what the motive is.”

Indeed, some in the industry consider the sought-after zoning changes too restrictive in terms of building size and scope. Specifically, they say that the allowance to purchase air rights should expand beyond the area immediately surrounding Grand Central to institutions including Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, Saint Bartholomew’s Church and Central Synagogue. “As the rezoning is presently drafted, I’d be shocked if two new buildings went up in the next 20 years,” Mr. Knakal said.

The D.C.P. under Mayor Michael Bloomberg introduced the amended Midtown East zoning strategy. But the biggest question on many REBNY members’ minds is who will lead New York after November’s election and whether City Hall’s next occupants will be as fervently pro-development as the current administration.

“The candidates who are likely to run are ones we can live with,” Mr. Spinola said. “We’ve got good relationships with the Democrat party leaders, and New York is traditionally a Democrat city, so we ought to be looking at Christine Quinn, Bill Thompson and Bill de Blasio.”

One industry source was less enthralled by Ms. Quinn, until recently considered Mayor Bloomberg’s anointed heir, saying she was only friendly to real estate interests when it deepened her pockets.

No matter how strong an alliance forms between Mr. Bloomberg’s successor and the real estate industry, the perceived threat among preservation advocates to Midtown’s landmarks and already strained infrastructure should make for a long and contentious debate.

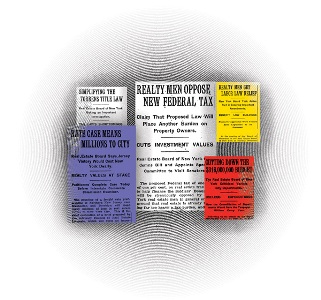

On the note of stubborn resistance to change, the real property tax rate remained a thorn in the commercial real estate industry’s collective side. Numbers provided by REBNY from the 2012 New York City property tax report revealed that Class 4 commercial properties paid 40 percent of the tax levy despite a 22 percent share of market value. Class 1 single-family homes had a 15 percent share of the levy and represented nearly half of the city’s total real estate value.

Not surprisingly, real estate professionals uniformly deem the tax implementation an intractable, inequitable and onerous problem. “Legislators look at income-producing properties as A.T.M. machines they can withdraw from to plug up budget deficits and other holes,” Mr. Knakal said. He added that while the tax rate—currently 10.288 percent for Class 4 properties—ostensibly remains more or less flat, politicians “instruct the Department of Finance to change assessment calculations that drive bills up.”

Even as the tax code stifles building owners’ revenues and vociferous proponents of civic-mindedly responsible development reject unchecked growth, REBNY’s numbers continue to mushroom. (The real estate industry made up nearly half of the city’s total revenue last year, compared with less than 20 percent in 1985, which helps explain its heaving ranks.) REBNY now counts 13,000 members, an all-time high.

Ms. Tighe’s three-year stewardship of the immense board drew uniformly high marks from officers and other real estate veterans who spoke to The Commercial Observer. Several cited Ms. Tighe’s encyclopedic knowledge of the local office market as her greatest asset.